from Apr. 22, 1865

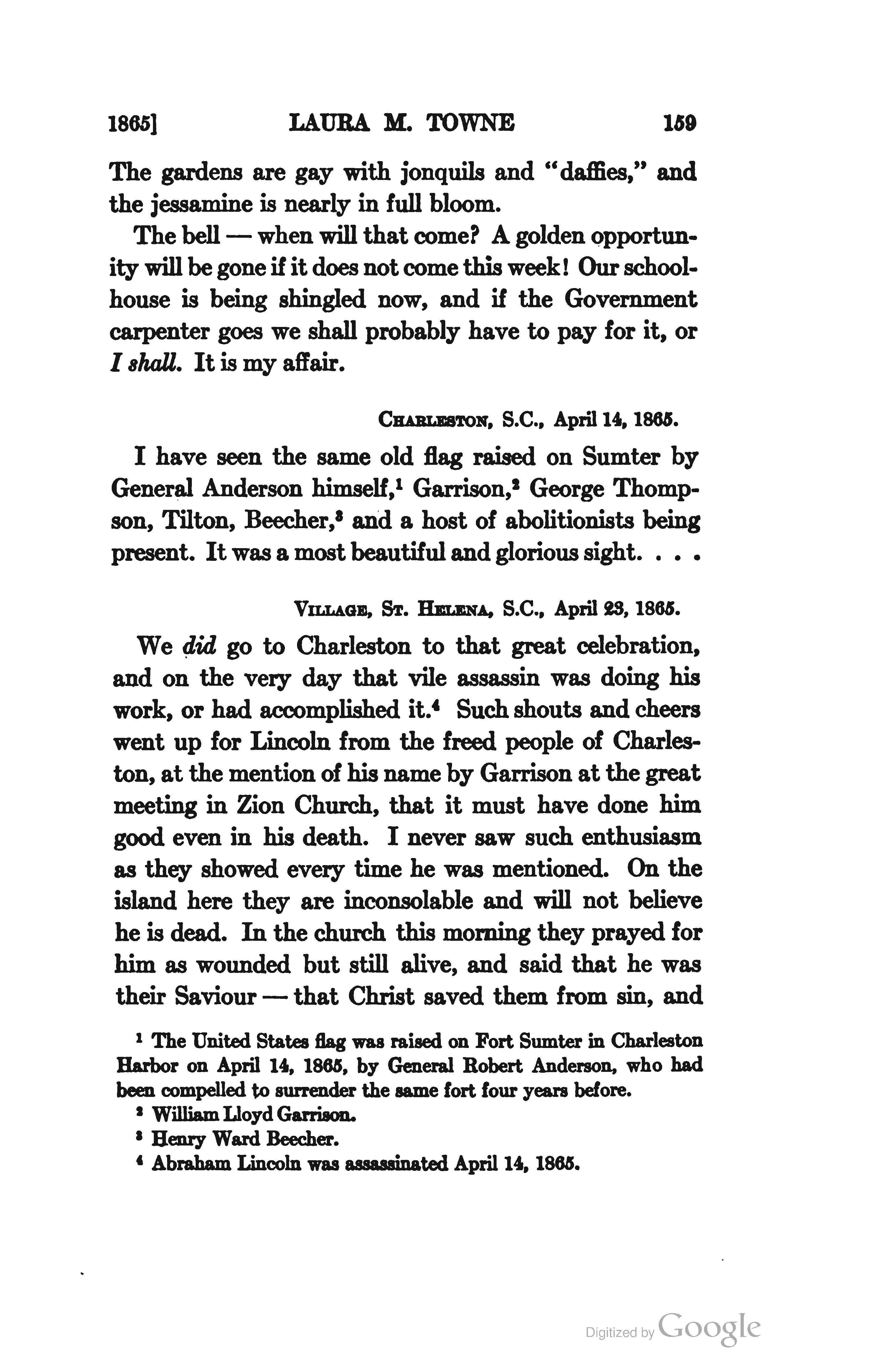

Excerpts from the Letters and diary of Laura M. Towne

-

Full Title

Excerpts from the Letters and diary of Laura M. Towne

-

Description

Laura M. Towne was an abolitionist and an educator. Before the Civil War, Towne was studying medicine but was motivated to become an abolitionist after the outbreak of the Civil War. Towne volunteered when the Union captured Port Royal and other Sea Islands area of South Carolina. She and her friend, Ellen Murray, founded the Penn Center on St. Helena Island, the first school for freed slaves. Her diaries and letters from this time were edited by Rupert Sargent Holland and published in 1912.

-

Transcription

The gardens are gay with jonquils and “daffies,” and the jessamine is nearly in full bloom.

The bell — when will that come? A golden opportunity will be gone if it does not come this week! Our schoolhouse is being shingled now, and if the Government carpenter goes we shall probably have to pay for it, or I shall. It is my affair.

Charleston, S.C., April 14, 1865.

I have seen the same old flag raised on Sumter by General Anderson himself,1 Garrison,2 George Thompson, Tilton, Beecher,3 and a host of abolitionists being present. It was a most beautiful and glorious sight…

Village, St. Helena, S.C., April 23, 1865.

We did go to Charleston to that great celebration, and on the very day that vile assassin was doing his work, or had accomplished it.4 Such shouts and cheers went up for Lincoln from the freed people of Charleston, at the mention of his name by Garrison at the great meeting in Zion Church, that it must have done him good even in his death. I never saw such enthusiasm as they showed every time he was mentioned. On the island here they are inconsolable and will not believe he is dead. In the church this morning they prayed for him as wounded but still alive, and said that he was their Saviour — that Christ saved them from sin, and

1. The United States flag was raised on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 14, 1865, by General Robert Anderson, who had been compelled to surrender the same fort four years before.

2. Willian Lloyd Garrison.

3. Henry Ward Beecher.

4. Abraham Lincoln was assassinated April 14, 1865.

----------------------------------

he from “Secesh,” and as for the vile Judas who had lifted his hand against him, they prayed the Lord the whirlwind would carry him away, and that he would melt as wax in the fervent heat, and be driven forever from before the Lord. Was n’t it the cunning of the Devil that did the deed; and they are going to prove him insane! When he was wise enough to strike the one in whom all could trust, and whose death would inevitably throw confusion and doubt into the popular mind of the North! And then to single out Seward2 in hopes that the next Secretary might embroil us with Europe and so give them another chance! It is so hard to wait a week or two before we know what comes next.

But I must tell you of our trip to Charleston. General Saxton gave us all passes, and a large party of teachers went from this island with Mr. Ruggles — good, kind, handsome fellow — to escort us. We stayed at a house kept by the former servants or slaves of Governor Aiken.

I was dreadfully seasick going up, and the day after I got there had to go to bed, and so I missed seeing many things I should have liked to visit. It stood — the house we stayed at —in the very heart of the shelled part of the city, and had ever so many balls through it. The burnt part of the town is the picture of desolation, and the detested “old sugar-house,” as the workhouse was called, looks like a giant in his lair. It was where all the slaves were whipped, and the whipping-room was made with double walls filled in with sand so that the cries could not be heard in the street. The treadmill and all

2 An attempt was also made to assassinate Secretary State Seward.

--------------------------------------------

kinds of tortures were inflicted there. I wanted to make sure of the building and asked an old black woman in that was the old sugar-house. “Dat’s it,” she said, “but it’s all played out now.” On Friday we went to Sumter, got good seats in the amphitheatre inside, near the pavilion for the speakers, and had a good opportunity to see all. I think there was not that enthusiasm in Anderson that I expected, and Henry Ward Beecher addressed himself to the “citizens of Charleston,” when there were not a dozen there. He spoke very much by note, and quite without fire.

At Sumter I bought several photographs, and send you one of the face [of the fortress] farthest from Wagner, Gregg, and our assailing forts, and consequently pretty well preserved. If you look closely you will see rows of basket-work, filled with sand, repairing a break. The whole inside of the fort is lined with them.

The next day was the grand day, however, when Wilson, Garrison, Thompson, Kelly, Tilton, and others spoke. Redpath mentioned John Brown’s name, and asked the great congregation to sing his favorite hymn, “Blow ye the Trumpet,” or “Year of Jubilee.”

I spoke to Judge Kelly afterwards and had a nice promise from him that he would send me all his speeches. We came home on Sunday and found all the missing boxes arrived,— or nearly all,— among them, mine. You do not know how intensely we all enjoy your picture—that exquisite sea-view. How could you spare me such a picture! I lie down on our sofa which faces it, and do so heartily enter into the freshness of it that it is refreshing in this hot weather. Many thanks to you.

------------------------------------------------

[The next letter refers to the death of President Lincoln.]

Saturday, April 29, 1865.

… It was a frightful blow at first. The people have refused to believe he was dead. Last Sunday the black minister of Frogmore said that if they knew the President were dead they would mourn for him, but they could not think that was the truth, and they would wait and see. We are going to-morrow to hear what further they say. One man came for clothing and seemed very indifferent about them — different from most of the people. I expressed some surprise. “Oh,” he said, “I have lost a friend. I don’t care much now about anything.” “What friend?” I asked, not really thinking for a moment. “They call him Sam,” he said; “Uncle Sam, the best friend ever I had.” Another asked me in a whisper if it were true that the “Government was dead.” Rina says she can’t sleep for thinking how sorry she is to lose “Pa Linkum.” You know they call their elders in the church—of the particular one who converted and received them in — their spiritual father, and he has the most absolute power over them. These fathers are addressed with feat and awe as “Pa Marcus,” “Pa Demas,” etc. One man said to me, “Lincoln died for we, Christ died for we, and me believe him de same mans,” that is, they are the same person.

We dressed our school-house in what black we could get, and gave a shred of crape to same of our children, who wear it sacredly. Fanny’s bonnet supplied the whole school.

[Transcription by: Grace C., Dr. Susan Corbesero’s Class, Ellis School, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania] -

Source

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Laura M. Towne. "Excerpts from the Letters and diary of Laura M. Towne". Cambridge, Printed at the Riverside Press,. Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1194

-

Creator

Laura M. Towne

-

Publisher

Cambridge, Printed at the Riverside Press,

-

Date

April 22, 1865

from Apr. 22, 1865

Excerpts from the Letters and diary of Laura M. Towne

-

Description

Laura M. Towne was an abolitionist and an educator. Before the Civil War, Towne was studying medicine but was motivated to become an abolitionist after the outbreak of the Civil War. Towne volunteered when the Union captured Port Royal and other Sea Islands area of South Carolina. She and her friend, Ellen Murray, founded the Penn Center on St. Helena Island, the first school for freed slaves. Her diaries and letters from this time were edited by Rupert Sargent Holland and published in 1912.

-

Source

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Laura M. Towne

-

Publisher

Cambridge, Printed at the Riverside Press,

-

Date

April 22, 1865

from Apr. 15, 1865

Susan B. Anthony's Diary

-

Full Title

Susan B. Anthony's Diary

-

Description

Susan B. Anthony was a women's rights activist and suffragette. Before and during the Civil War, she was also heavily involved in the anti-slavery movement. She wrote about the Lincoln assassination in her diary after she learned of the news on April 15th and over the following days.

-

Source

Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Susan B. Anthony Papers

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Susan B. Anthony. "Susan B. Anthony's Diary". Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1189

-

Creator

Susan B. Anthony

-

Date

April 15, 1865

from Apr. 15, 1865

Susan B. Anthony's Diary

-

Description

Susan B. Anthony was a women's rights activist and suffragette. Before and during the Civil War, she was also heavily involved in the anti-slavery movement. She wrote about the Lincoln assassination in her diary after she learned of the news on April 15th and over the following days.

-

Source

Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Susan B. Anthony Papers

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Susan B. Anthony

-

Date

April 15, 1865

from Jun. 1, 1865

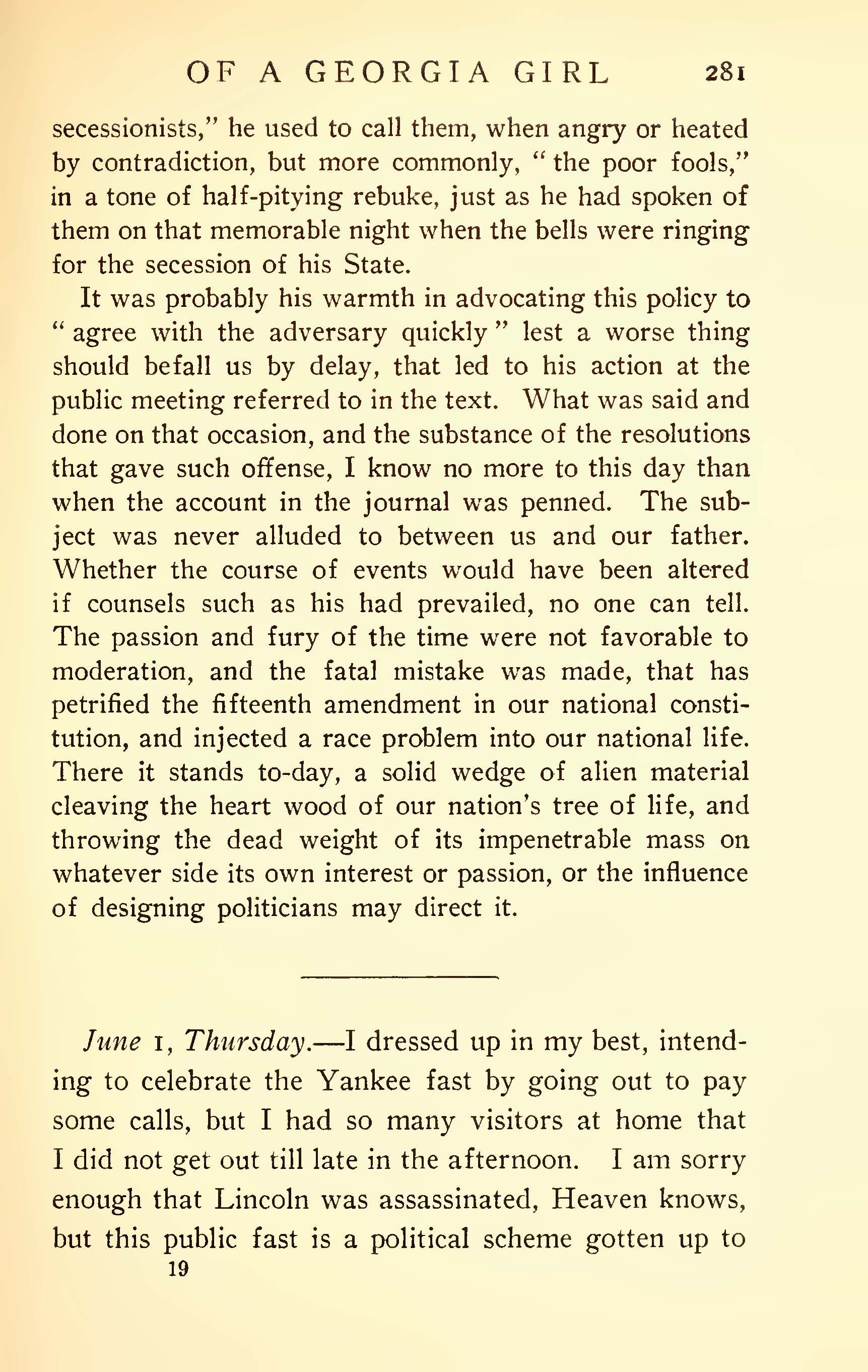

Excerpt from The War-time Journal of a Georgia girl, 1864-1865

-

Full Title

Excerpt from The War-time Journal of a Georgia girl, 1864-1865

-

Description

Eliza Frances Andrews was born in Washington, Georgia in 1840. Her father was a prominent judge and planter. While her parents supported the Union, she and her three brothers supported the Confederacy. Her journal begins with her journey to Macon, Georgia in December 1864 to meet relatives with whom she would stay until the War ended. Her journal was heavily edited and published 40 years later. However, it gives insight into Andrews reaction to the Lincoln Assassination and to his memorial on June 1, 1865.

-

Transcription

The War-time Journal of a Georgia girl 1864 dash 1865 by Eliza Frances Andrews

… Secessionists,” he used to call them, when angry or heated By contradiction, but more commonly, “the poor fools,” in a tone of half-pitying rebuke, just as he had spoken of them on that memorable night when the bells were ringing for the secession of his State.

It was probably his warmth in advocating this policy to “agree with the adversary quickly” lest a worse thing should befall us by delay, that led to his action at the public meeting referred to in the text. What was said and done on that occasion, and the substance of the resolutions that gave such offense, I know no more to this day than when the account in the journal was penned. The subject was never alluded to between us and our father. Whether the course of events would have been altered if councils such as his had prevailed, no one can tell. The passion and fury of the time were not favorable to moderation, and the fatal mistake was made, that has petrified the fifteenth amendment in our national constitution comma and injected a race problem into our national life. There it stands to-day, a solid wedge of alien material cleaving the heartwood of our nation's tree of life, and throwing the dead weight of its impenetrable mass on whatever side its own interests or passion, or the influence of designing politicians may direct it.

June 1, Thursday. –I dressed up in my best, intending to celebrate the Yankee fast by going out to pay some call, but I had so many visitors at home that I did not get out till late in the afternoon. I’m sorry enough that Lincoln was assassinated, Heaven knows, but in this public fast is a political scheme gotten up to throw reproach on the South comma and I wouldn't keep it if I were ten times as sorry as I am.

The “righteous Lot” Has come back to town. It is uncertain whether he or Capt. Schaeffer is to reign over us; we hope the latter. He is said to be a very gentlemanly-looking person, and above associating with negroes. his men look cleaner than the other garrison, but Garnett saw one of them with a lady’s gold bracelet on his arm, which shows what they are capable of. I never look at them, but always turn away my head, or pull down my veil when I meet any of them period the streets are so negroes That I don't like to go out when I can help it, though they seem to be behaving better about Washington than in most other places. Capt. Schaeffer does not encourage them in leaving their Masters, still, many of them try to play at freedom, and give themselves airs that are exasperating. The last time I went on the street, two great, strapping wenches forced me off the sidewalk. I could have raised a row by calling for protection from the first Confederate I met, or making complaint at Yankee headquarters, but would not stoop to quarrel with negroes. If the question had to be settled By these Yankees who are in the South comma and see the working of things, I do not believe emancipation would be forced on us in such a hurry; but unfortunately, the government is in the hands of a set of crazy abolitionists, who will make a pretty mess, meddling with things they know nothing about. Some of the Yankee generals have already been converted from their abolition sentiments, and it is said that Wilson is deviled all by out of his life by the negroes in South-West Georgia. In Atlanta, Judge Irvin says he saw the corpses of two dead negroes kicking about the streets unburied, waiting for the public ambulance to come and cart them away.

June 4, Sunday. –Still another batch of Yankees comma and one of them preceded to distinguish himself at once, by “capturing” a negro's watch. They carry out their principles by robbing impartially, without regard to “race, color, or previous condition.” ’Ginny Dick had kept his watch and chain hid ever since the bluecoats put forth this act of philanthropy, and George Palmer's old Maum Betsy said that she has “knowned white folks all her life, an’ some mighty mean ones, but Yankees is de fust ever she seed mean enough to steal fum niggers.” Everybody suspected that mischief was afoot, as soon as the Yankees began coming in such force, and they soon fulfilled expectations by going to the bank and seizing $100,000 in specie belonging to the Virginia banks, which the Confederate calvarymen had restored as soon as they found it was private property. They then arrested the Virginia bank officers, and went about town “pressing” people’s horses to take them to Danburg, to get the “robbers” and the rest of the money, which they say is concealed there. One of the men came to our house after supper, while we were sitting out on…

[Transcription by Quoc T., Ford’s Theatre Society.]

-

Source

Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection via The Internet Archive

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Eliza Frances Andrews. "Excerpt from The War-time Journal of a Georgia girl, 1864-1865". New York : D. Appleton and Company. Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1188

-

Creator

Eliza Frances Andrews

-

Publisher

New York : D. Appleton and Company

-

Date

June 1, 1865

from Jun. 1, 1865

Excerpt from The War-time Journal of a Georgia girl, 1864-1865

-

Description

Eliza Frances Andrews was born in Washington, Georgia in 1840. Her father was a prominent judge and planter. While her parents supported the Union, she and her three brothers supported the Confederacy. Her journal begins with her journey to Macon, Georgia in December 1864 to meet relatives with whom she would stay until the War ended. Her journal was heavily edited and published 40 years later. However, it gives insight into Andrews reaction to the Lincoln Assassination and to his memorial on June 1, 1865.

-

Source

Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection via The Internet Archive

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Eliza Frances Andrews

-

Publisher

New York : D. Appleton and Company

-

Date

June 1, 1865

from May. 1, 1865

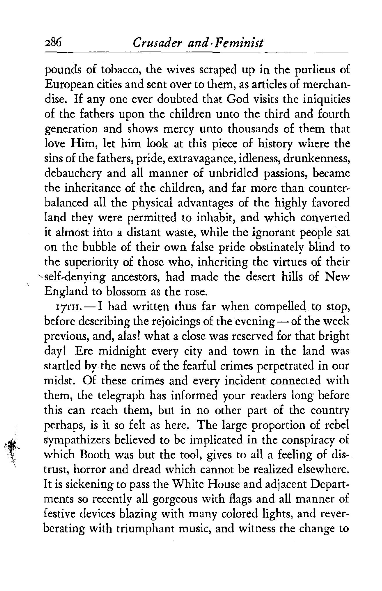

Letters of Jane Grey Swisshelm

-

Full Title

Excerpts from Crusader and feminist; letters of Jane Grey Swisshelm, 1858-1865;

-

Description

Jane Grey Swisshelm a journalist was the editor of the Cloud Visiter [sic] and, afterward, the St. Cloud Democrat. The Minnesota Historical Society collected and compiled the series of articles and letters written for the St. Cloud Democrat, publishing them as a book in 1934. Her letters from late April and early May 1865, express her grief over Lincoln's death and her fear for the country's future.

-

Source

Library of Congress, General Collections and Rare Book and Special Collections Division

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Jane Grey Swisshelm. "Excerpts from Crusader and feminist; letters of Jane Grey Swisshelm, 1858-1865;". The Minnesota Historical Society. Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1186

-

Creator

Jane Grey Swisshelm

-

Publisher

The Minnesota Historical Society

-

Date

April-May 1865

from May. 1, 1865

Excerpts from Crusader and feminist; letters of Jane Grey Swisshelm, 1858-1865;

-

Description

Jane Grey Swisshelm a journalist was the editor of the Cloud Visiter [sic] and, afterward, the St. Cloud Democrat. The Minnesota Historical Society collected and compiled the series of articles and letters written for the St. Cloud Democrat, publishing them as a book in 1934. Her letters from late April and early May 1865, express her grief over Lincoln's death and her fear for the country's future.

-

Source

Library of Congress, General Collections and Rare Book and Special Collections Division

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Jane Grey Swisshelm

-

Publisher

The Minnesota Historical Society

-

Date

May 1, 1865

from Apr. 20, 2018

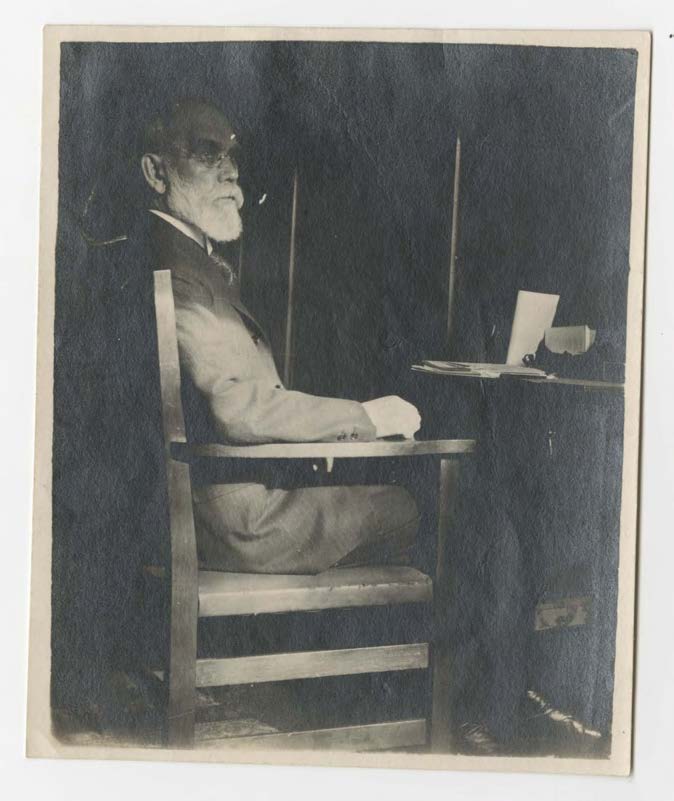

Lincolniana Collection of Katherine Pope

-

Full Title

Lincolniana Collection of Katherine Pope

-

Description

Katherine Pope collected a stories, photographs, and poems from Chicago residents who knew Lincoln.

-

Source

Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Katherine Pope. "Lincolniana Collection of Katherine Pope". Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1181

-

Creator

Katherine Pope

-

Date

April 20, 2018

from Apr. 20, 2018

Lincolniana Collection of Katherine Pope

-

Description

Katherine Pope collected a stories, photographs, and poems from Chicago residents who knew Lincoln.

-

Source

Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Katherine Pope

-

Date

April 20, 2018

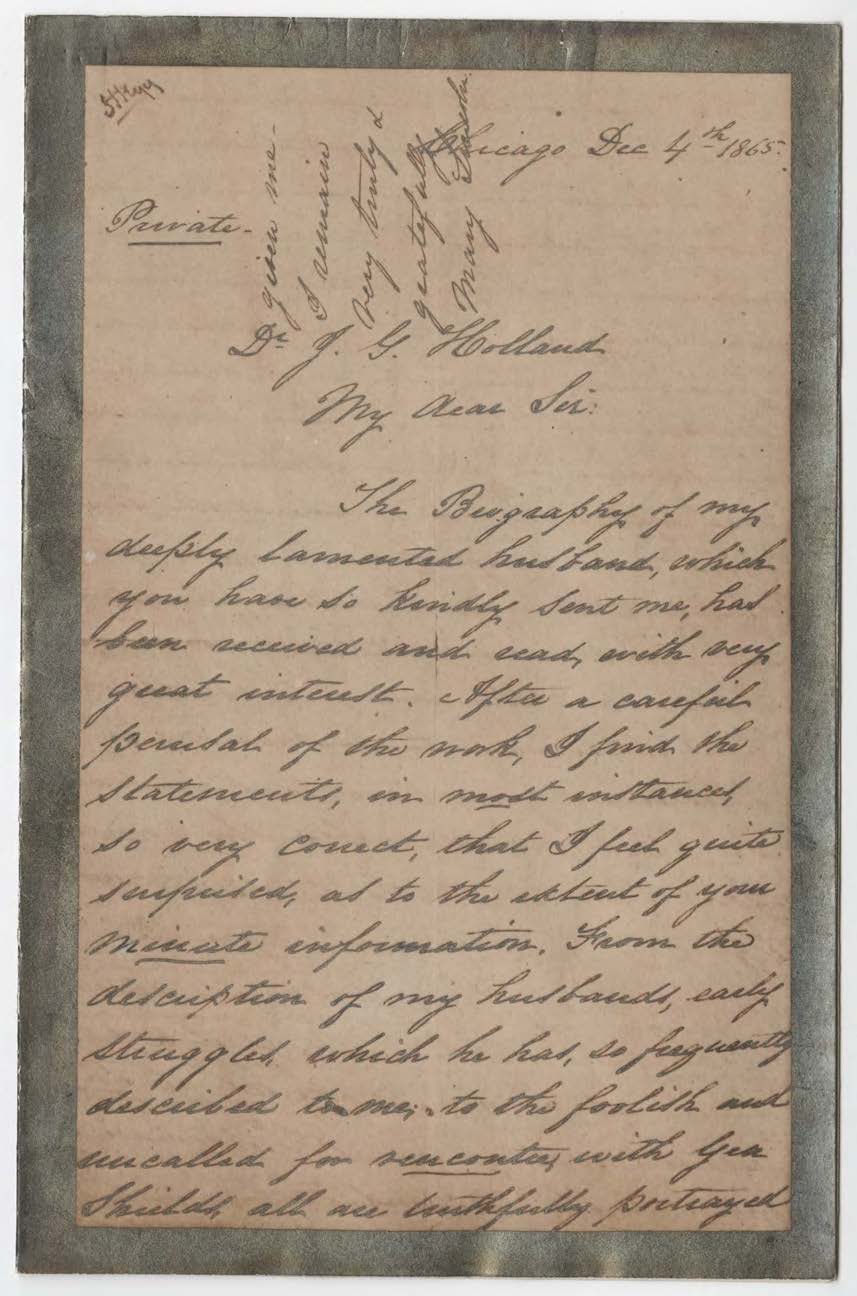

from Dec. 4, 1865

Mary Todd Lincoln to Dr. Josiah G. Holland

-

Full Title

Mary Todd Lincoln to Dr. Josiah G. Holland

-

Description

A letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Dr. Josiah G. Holland after receiving a copy of Holland's biography of her husband, the Life of Abraham Lincoln.

-

Transcription

Chicago Dec 4th 1865

Private –

Dr. J. G. Holland

My dear Sir:

The Biography of my deeply lamented husband, which you have so kindly sent me, has been received and read, with very great interest. After a careful perusal of the work, I find the statements, in most instances, so very correct, that I feel quite surprised, as to the extent of your minute information. From the description of my husband, early struggles, which he has, so frequently described to me, to the foolish and uncalled for rencontre, with Gen Shields, all are truthfully portrayed.

It is exceedingly painful to me, now suffering under such an overwhelming bereavement, to recall that happy time my beloved husband had so entirely devoted himself to one, for two years before my marriage, that I doubted trespassed, many times & oft, upon his great tenderness & amiability of character. There never existed a more loving & devoted husband & such a Father, has seldom been bestowed on children. Crushed and bowed to the earth, with our great great sorrow, for the sake of my poor afflicted boys, I have to strive to live on, and comfort them, as well as I can. You are aware that with all the President’s deep feeling, he was not a demonstrative man, when he felt most deeply, he expressed the least. There are some very good persons who are inclined to magnify conversations & incidents, connected with their slight acquaintance with this great & good man. For instance, the purported conversations This last event, occurred about six months before our marriage, when, Mr. Lincoln thought he had some right to assume to be my champion, even on frivolous occasions. The poor Gent, in our little gay circle, was oftentimes, the subject of mirth & even song. And we were then surrounded by several of those, who have since been appreciated by the world. The Gent was very impulsive & on the occasion referred to, had placed himself before us, in so ridiculous a light, that the love of the ludicrous had been excited within me & I pressure, I gave vent to it, in some very silly levies. After the reconciliation between the contending parties Mr L & myself mutually agreed never to refer to it & except in an occasional light manner, between us, it was never mentioned. I am surprised at so distant a day, you should have ever heard of the circumstance.

Between the President & the Hospital nurse, it was not his nature to commit his griefs and religious feelings so fully to words & that with an entire stranger. Even between ourselves, when our deep & touching sorrows were one & the same, his expressions were few – Also the lengthy account of the lady who very wisely persisted in claiming a hospital for her State, my husband never had the time to discuss these matters, so lengthily to any person or persons-- too many of them came daily in review before him – And again, I cannot understand how strangely his temper could be at so complete a variance from what it always was, in the home circle. There he was always so gentle & kind. Before closing this long letter which I fear will weary you, ___ you get through it – allow me again to assure you of the great satisfaction the perusal of your Memoirs have given me.

I remain very truly and gratefully,

Mary Lincoln

[Transcription by Susan Brady Carr] -

Source

Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Mary Todd Lincoln. "Mary Todd Lincoln to Dr. Josiah G. Holland". Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1179

-

Creator

Mary Todd Lincoln

-

Date

December 4, 1865

from Dec. 4, 1865

Mary Todd Lincoln to Dr. Josiah G. Holland

-

Description

A letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Dr. Josiah G. Holland after receiving a copy of Holland's biography of her husband, the Life of Abraham Lincoln.

-

Source

Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Mary Todd Lincoln

-

Date

December 4, 1865

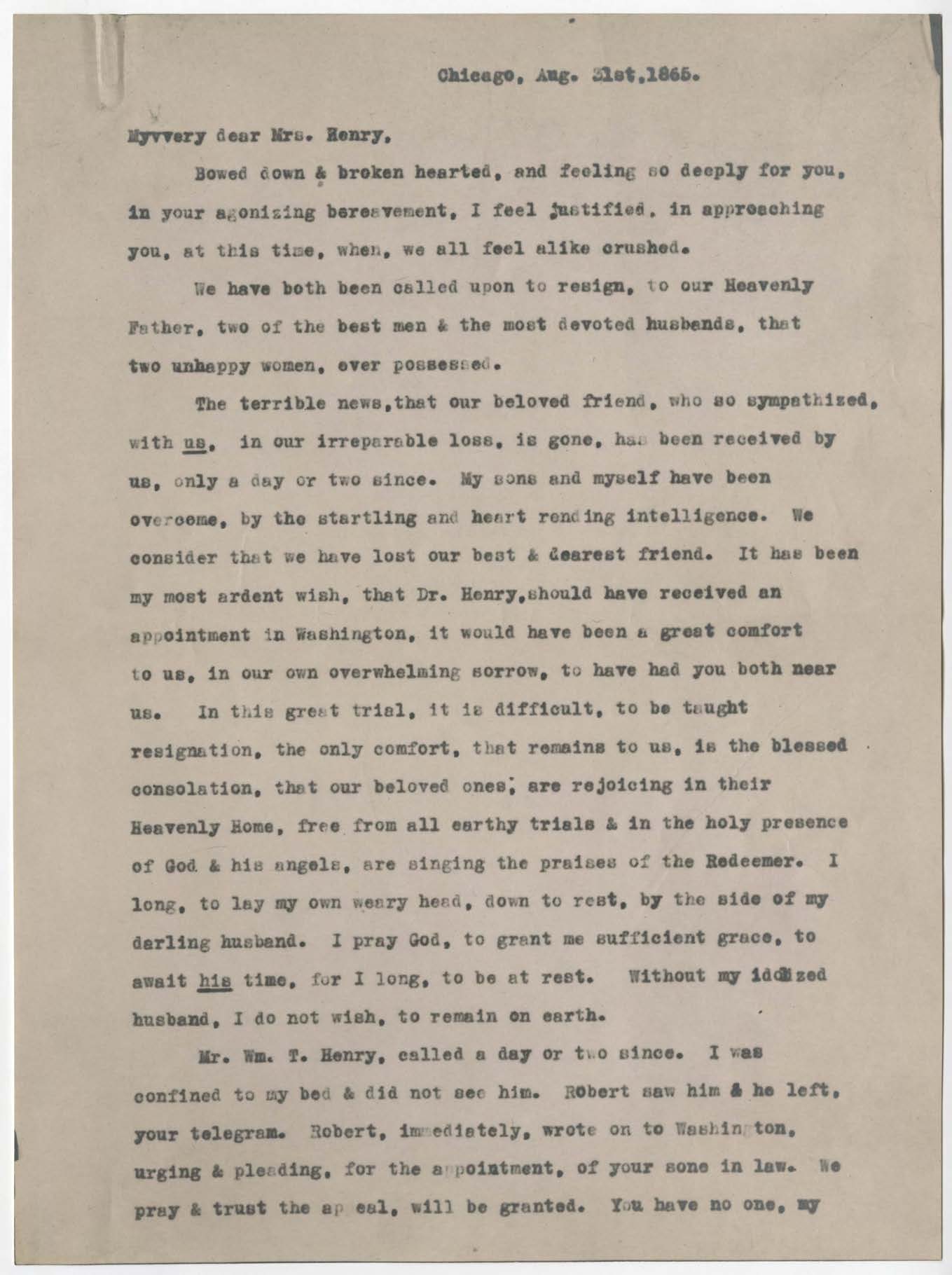

from Aug. 31, 1865

A Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Mrs. Anson G. Henry

-

Full Title

A Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Mrs. Anson G. Henry

-

Description

A Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Mrs. Anson G. Henry. Mrs. Henry's husband was a friend of Abraham Lincoln and the Surveyor General of Washington Territory at the time of Lincoln's death. Dr. Henry died on July 30, 1865. Mary Lincoln's letter expresses her sympathy for Mrs. Henry and her own grief for the death Dr. Henry and her husband.

-

Transcription

Chicago, Aug 31st 1865.

My very dear Mrs. Henry,

Bowed down and broken hearted, and feeling so deeply for you, in your agonizing bereavement, I feel justified in approaching you at this time when we all feel I’ll alike crushed.

We’ve have both been called upon to resign, to our Heavenly Father, two of the best men & the most devoted husbands that too unhappy women ever possessed.

The terrible news that our beloved friend who so sympathized with us in our irreparable loss, is gone, has been received by us, only a day or two since. My sons and myself have been overcome, by the startling and heart rendering intelligence. We consider that we have lost our best & dearest friend. It has been my most ardent wish that Dr. Henry should have received an appointment in Washington, it would have been a great comfort to us, in our own overwhelming sorrow to have had you both near us. In this great trial, it is difficult, to be taught resignation, the only comfort, that remains to us is the blessed consolation, that our beloved ones, are rejoicing in their Heavenly Home, free from all earthly trials & in the holy presence of God & his angels, are singing the praises of the Redeemer. I long, to lay my own weary head, down to rest, by the side of my darling husband. I pray God, to grant me sufficient grace, to await his time, for I long, to be at rest. Without my idolized husband, I do not wish to remain on earth.

Mr. Wm. T. Henry, called a day or two since. I was confined to my bed & did not see him. Robert saw him & he left, your telegram. Robert, immediately, wrote on to Washington, urging & pleading, for the appointment, of your son in law. We pray & trust the appeal, will be granted. You have no one, my dear friend, who could possibly feel for you, as I do, your grief is mine, in it, I am living over my own disconsolate state & the gratitude we feel for the dear Doctor’s recent sympathy, for us, in all things together with the great love, we all bore him, makes your troubles my own. How much, I wish, you lived nearer to us. We could then, weep, together over our dreary lot. The world, without my beloved husband & our best friend, is a sad and lonely place enough.

Our poor little family, would be a gloomy picture, for any one to see, who has a heart to feel. It was a great trial, to me, when Dr. Henry left here in June, that I was unable to have access to some boxes, stored in the warehouse, where was deposited a cane of my husband’s, a large family Bible & some other things design for presentation, to the Dr. So soon as I can get to them, I shall avail myself, of the first opportunity, of sending them to you. I can offer you in conclusion, of this very sad letter, my dear Mrs. Henry, very little consolation, for I am so weary & heavy laden myself, over everything, concerning us both. I trust you will write me to me, for you are very dear to me, now & ever.

With regards to your family, I remain always

Your attached friend,

Mary Lincoln.

[Transcription by Alicia B., Ford's Theatre Society, and Janet Scanlon.] -

Source

Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Mary Todd Lincoln. "A Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Mrs. Anson G. Henry". Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1178

-

Creator

Mary Todd Lincoln

-

Date

August 31, 1865

from Aug. 31, 1865

A Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Mrs. Anson G. Henry

-

Description

A Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Mrs. Anson G. Henry. Mrs. Henry's husband was a friend of Abraham Lincoln and the Surveyor General of Washington Territory at the time of Lincoln's death. Dr. Henry died on July 30, 1865. Mary Lincoln's letter expresses her sympathy for Mrs. Henry and her own grief for the death Dr. Henry and her husband.

-

Source

Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Mary Todd Lincoln

-

Date

August 31, 1865

from Apr. 16, 1865

Lincoln's Assassination Told by an Eye Witness

-

Full Title

Lincoln's Assassination Told by an Eye Witness

-

Description

A letter written by Julia Adelaide Shepard who was in attendance at Ford's Theatre on April 14, 1865. She wrote to her father on the 16th recounting the Lincoln Assassination. It was printed in The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine Volume 77 (Nov. 1908 - April 1909)

-

Transcription

LINCOLN’S ASSASSINATION

TOLD BY AN EYE-WITNESS

The letter which follows was written on the date given, by Miss Julia Adelaide Shepard, now living in Ogdensburg, New York. Miss Shepard is an aunt of the artist, Mr. Charles S. Chapman, through whose good offices we are enabled to make it public the first time. – THE EDITOR.

“Hopeton” near Washington.

April 16, 1865

DEAR FATHER: - It is Friday night and we are at the theatre. Cousin Julia has just told me that the President is in yonder upper right hand private box so handsomely decked with silken flags festooned over a picture of Washington. The young and lovely daughter of Senator Harris is the only one of the party we can see, as the flags hide the rest. But we know that “Father Abraham” is there; like a father watching what interests his children, for their pleasure rather than his own. It has been announced in the papers that he would be there. How sociable it seems, like one family sitting around their parlor fire. How different this from the pomp and show of monarchial Europe. Every one has been so jubilant for days, since the surrender of Lee, that they laugh and shout at every clown-ish witticism. One of the actresses, whose part is that of a very delicate young lady, talks of wishing to avoid the draft, when her lover tells “not to be alarmed for there is no more draft, “ at which the applause is long and loud. The American cousin has just been making love to a young lady, who says she will never marry but for love, yet when her mother and herself find he has lost his property they retreat in disgust at the left of the stage, while the American cousin goes out at the right. We are waiting for the next scene.

The report of a pistol is heard…. Is it all in the play? A man leaps from the President’s box, some ten feet, on to the stage. The truth flashes upon me. Brandishing a dagger he shrieks out “The South is avenged,” and rushes through the scenery. No one stirs. “Did you hear what he said, Julia? I believe he has killed the President.” Miss Harris is wringing her hands and calling for water. Another instant and the stage is crowded – officers, policemen, actors and citizens. “Is there a surgeon in the house?” they say. Several rush forward and with superhuman efforts climb up to the box. Minutes are hours, but see! they are bringing him out. A score of strong arms bear Lincoln’s loved form along. A glimpse of a ghastly face is all as they pass along…. Major Rathbone, who was of their party, springs forward to support [Mrs. Lincoln], but cannot. What is it? Yes, he too has been stabbed. Somebody says “Clear the house,” so every one else repeats “Yes, clear the house.” So slowly one party after another steals out. There is no need to hurry. On the stairs we stop aghast and with shuddering lips – “Yes, see, it is our President’s blood” all down the stairs and out upon the pavement. It seemed sacrilege to step near. We are in the street now. They have taken the President into the house opposite. He is alive, but mortally wounded. What are those people saying, “Secretary Seward and his son have had their throats cut in their own house.” Is it so? Yes, and the mur-derer of our President has escaped through a back alley where a swift horse stood awaiting him. Cavalry come dashing up the street and stand with drawn swords before yon house. Too late! too late! What a mockery armed men are now. Weary with the weight of woe the moments drag along and for hours delicate women stand cling-ing to the arms of their protectors and strong men throw their arms around each other’s necks and cry like children, and passing up and down enquire in low agon-ized voices “Can he live? Is there no hope?” They are putting out the street lamps now. “What a shame! not now! not to-night!” There they are lit again. Now the guard with the drawn swords forces the crowd backward. Great, strong Cousin Ed says “This unnerves me; let’s go up to Cousin Joe’s.” We leave Julia and her escort there and at brother Joe’s gather together in an upper room and talk and talk with Dr. Webb and his wife who were at the theatre. Dr. W. was one of the surgeons who answered the call. He says “I asked Dr. ____ when I went in what it was, and putting his hand on mine he said, “There!” I looked and it was ‘brains.’ “

After a while Julia and Mr. W came in and still we talked and listened to the cavalry rushing through the echoing street. Joe was determined to go out, but his wife couldn’t endure the thought of any one going out of the house. It was only in the early hours of the dawn that the gentlemen went to lie down, but Julia sat up in a rocking chair and I lay down on the outside of the bed beside Cousin Ginny for the rest of the night, while Cousin Joe and his wife’s young brother sat nodding in chairs opposite. There were rooms waiting for us but it seemed safer to be together. He was still living when we came out to Hopeton, but we had scarcely choked down our break-fast next morning when the tolling bells announced the terrible truth.

Last Thursday evening we drove to the city, and all along our route the city was one blaze of glorious light. From the humble cabin of the contraband to the brilliant White House light answered light down the broad avenue. The sky was ablaze with bursting rockets. Calcium lights shone from afar on the public buildings. Bonfires blazed in the streets and every device that human Yankee ingenuity could suggest in the way of mottoes and decoration made noon of midnight. Then as candles burned low and rockets ceased, we drove home through the balmy air and it seemed as though Heaven smiled upon the rejoic-ings, and Nature took up the illumination with a glory of moonlight that tran-scended all art.

To-day I have been to church through the same streets and the suburbs with the humble cottages that were so bright that night shone through the murky morning, heavy with black hangings, and on and on, down the streets only the blackness of darkness. The show of mourning was as universal as the glorying had been, and when we were surrounded by the sol-emn and awe-stricken congregation in the church, it seemed as through my heart had stopped beating. I feel like a fright-ened child. I wish I could go home and have a good cry. I can’t bear to be alone. You will hear all of this from the papers, but I can’t help writing it for things seen are mightier than things heard. It seems hard to write now. I dare not speak of our great loss. Sleeping or waking, that terrible scene is before me.

[Transcription by Alicia B., Ford's Theatre Society.] -

Source

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Julia Adelaide Shepard. "Lincoln's Assassination Told by an Eye Witness ". The Century Company, New York. Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1169

-

Creator

Julia Adelaide Shepard

-

Publisher

The Century Company, New York

-

Date

April 16, 1865

from Apr. 16, 1865

Lincoln's Assassination Told by an Eye Witness

-

Description

A letter written by Julia Adelaide Shepard who was in attendance at Ford's Theatre on April 14, 1865. She wrote to her father on the 16th recounting the Lincoln Assassination. It was printed in The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine Volume 77 (Nov. 1908 - April 1909)

-

Source

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Julia Adelaide Shepard

-

Publisher

The Century Company, New York

-

Date

April 16, 1865

from Apr. 15, 1865

Letter from "Mary" to "Sister"

-

Full Title

Letter from "Mary" to "Sister"

-

Description

In this Letter a young woman, Mary, living in Washington, D.C. writes her sister, expressing her grief over Lincoln's assassination and tells of the atmosphere of mourning in the city. She goes on to relate her own account of the night of the assassination.

-

Transcription

Saturday Morning

Washington April 15th 1865

My Dear Sister

Long ere this reaches you the news of the Nations terrible calamity will have flashed to the remotest corner of the United States of the dastardly murder of our dearly beloved President not in Richmond among his enemies but in Washington and among his avowed friends. The heart of the an nation throbs with greif at a loss it cannot soon repair but if you could look into the faces of those here today you would see that he was loved most dearly by those who knew him best. I have just passed in sight of the house where little less than an hour ago the nations heart and life ceased to beat for its welfare. Oh the agony depicted on the faces of that crowd. Men actualy tearing their hair from very greif and agony. The state of feeling is such that it is impossible to tell what it may lead to after what is past it is not safe to judge what a day may bring forth. The streets are patroled to keep the people (and its not the roughs) from assasinating every known simpathizer with the rebelion. The whole city is being draped in the heaviest mourning the bells are tolling and every-thing and every-body wears the sadest aspect a human eye ever looked upon.

I was at Grovers Theatre at the time this desperately wicked act was perpetrated at Fords. The alarm was given and instantly the people rushed to the doors supposing the building was on fire people were thrown down stairs and the wildest confusion prevailed. I was never more frightend in my life yet I stood back thinking it was as well to stand my chance of escaping the fire as to be killed in the dense crowd when the excitement had subsided the audience took their seats without knowing what had occured and the play went on for about 15 minutes when the manager came forward and announced that the President had been assasinated and a scene ensued beyond description strong men wept like little children it was a scene which I shall remember to my latest breath. there were few pillows that were not wet with tears of true sorrow while none were visited with sleep, of those who knew of it words would fail to express the horror and indignation which pervades the entire community

What a change in one short day. Yesterday all was bright and joyous today, gloom and sorrow cover a nation.

Yesterday was a lovely day, today is dark and cloudy. It seems as if the sun refused to shine on the dark deed.

I must close for I am nervous and hardly know how I have written what I have. I have changed my boarding place so you must direct to the pension Office give my love to Mother write me if she is not well for I have felt worried since her last letter she wrote so sadly. write soon. from yours

Off, Mary

-

Source

National Park Service, Ford's Theatre National Historic Site

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Mary . "Letter from "Mary" to "Sister"". Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1131

-

Creator

Mary

-

Date

April 15, 1865

from Apr. 15, 1865

Letter from "Mary" to "Sister"

-

Description

In this Letter a young woman, Mary, living in Washington, D.C. writes her sister, expressing her grief over Lincoln's assassination and tells of the atmosphere of mourning in the city. She goes on to relate her own account of the night of the assassination.

-

Source

National Park Service, Ford's Theatre National Historic Site

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Mary

-

Date

April 15, 1865

from May. 1, 1865

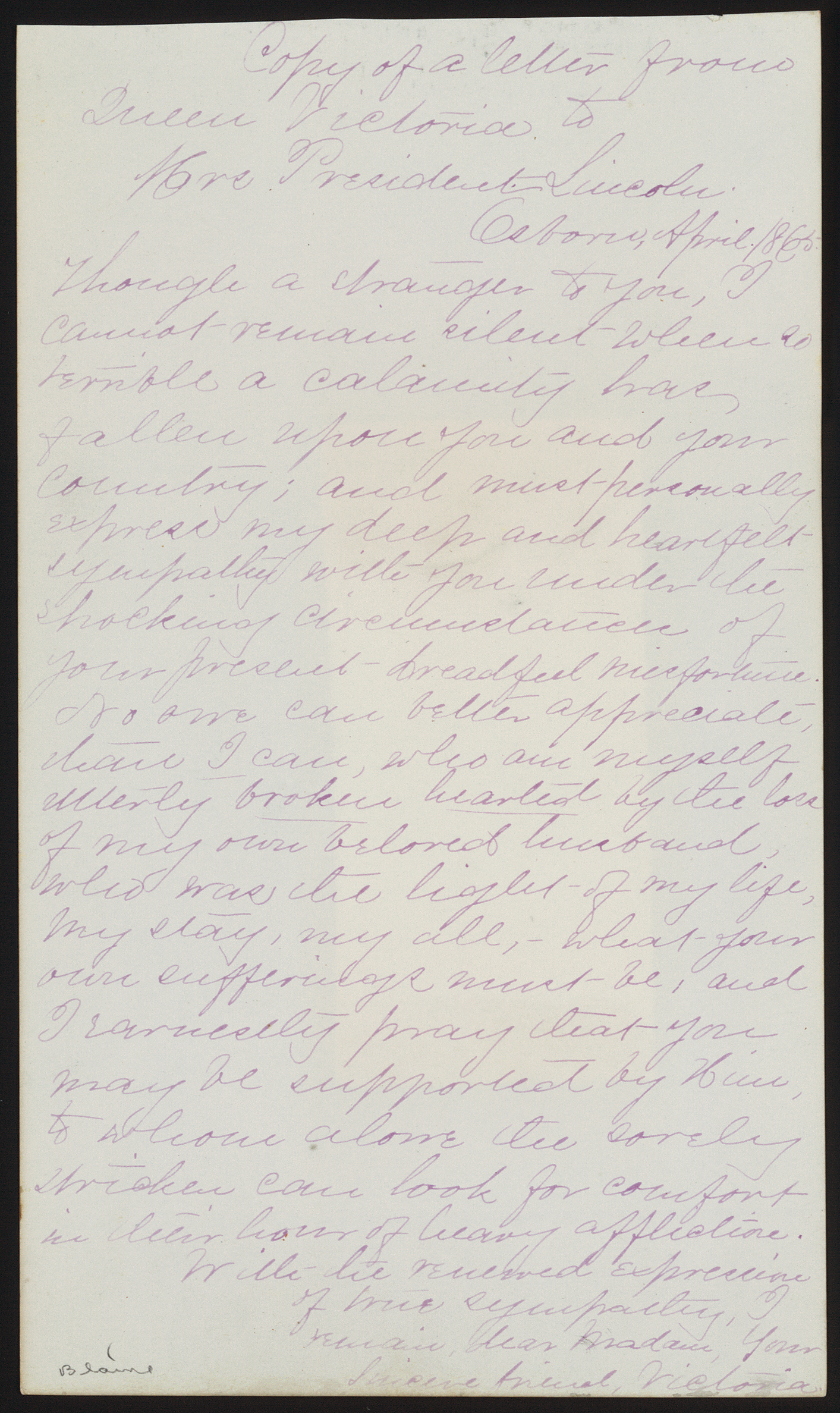

Letter to Mary Todd Lincoln from Queen Victoria

-

Full Title

Letter to Mary Todd Lincoln from Queen Victoria

-

Description

Manuscript transcription of a letter from Queen Victoria to Mrs. Abraham Lincoln, written in purple ink on white woven paper. Queen Victoria, the British monarch, wrote to Mary Lincoln after learning about the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The two women had never met, but Queen Victoria wanted to convey her sympathies to Mrs. Lincoln because she also lost her husband in 1861 and went into intense mourning.

-

Transcription

Copy of a letter from Queen Victoria to Mrs. President Lincoln Osborne, April. 1865

Thought a stranger to you, cannot remain silent w[?] so terrible a calamity has fallen upon you and your country; and must personally express my deep and heartfelt sympathy wi[?] you under shocking circumstances of your present— dreadful misfortune. No one can better appreciate, than I can, who am myself utterly broken hearted by the loss of my own beloved husband, who was the light of my life, my stay, my all, —what your own sufferings must be, and I earnestly pray that you may be supported by Him, to whom alone the sorely stricken can look for comfort in their hour of heavy afflication.

With the renewed expression of true sympathy, I remain, dear Madam, Your sincere friend, Victoria -

Source

Library of Congress

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Queen Victoria. "Letter to Mary Todd Lincoln from Queen Victoria". Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1108

-

Creator

Queen Victoria

-

Date

1865

-

Dimensions

21 x 11 cm

from May. 1, 1865

Letter to Mary Todd Lincoln from Queen Victoria

-

Description

Manuscript transcription of a letter from Queen Victoria to Mrs. Abraham Lincoln, written in purple ink on white woven paper. Queen Victoria, the British monarch, wrote to Mary Lincoln after learning about the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The two women had never met, but Queen Victoria wanted to convey her sympathies to Mrs. Lincoln because she also lost her husband in 1861 and went into intense mourning.

-

Source

Library of Congress

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Queen Victoria

-

Date

May 1, 1865

-

Dimensions

21 x 11 cm