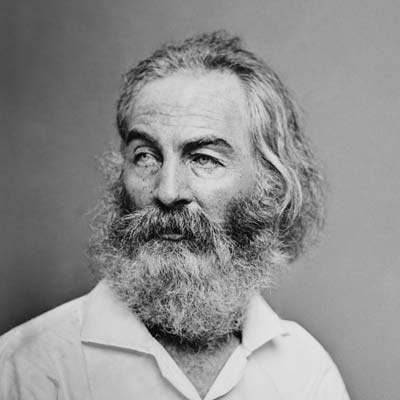

Walt Whitman

Many students read “Oh Captain, My Captain”—but often don’t realize that Walt Whitman composed that poem to capture his emotions at hearing of President Lincoln’s assassination. Whitman, already a famous poet, served as a volunteer nurse in Washington, seeing the horrors of war firsthand as he tended to wounded soldiers.

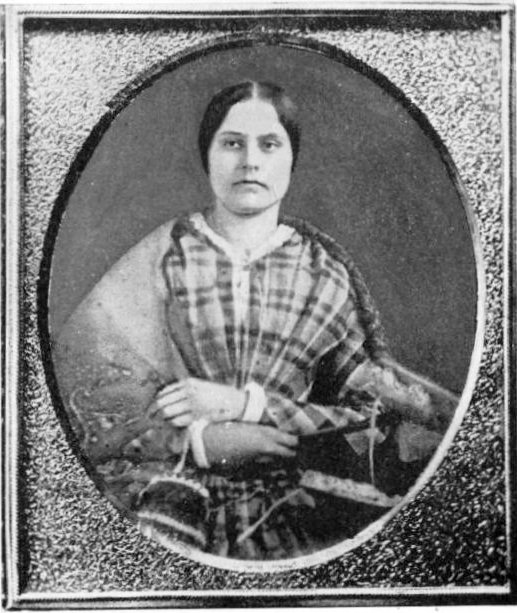

Sarah Gooll Putnam

As an adult, Sarah Gooll Putnam made a living as a portraitist. One of her earliest works appears in her April 15, 1865, diary entry, when she was 13 or 14. She depicted the look on her face when she learned of Lincoln’s death from her father in Boston.

Mary Henry

Mary Henry literally observed Washington from a castle. The daughter of the Smithsonian’s Secretary, Joseph Henry, Mary kept a diary during the Civil War. She succinctly captured how Washingtonians moved from joy at the end of the war to mourning the slain president.

Moses Many Lightning Face

At the close of the Dakota War of 1862, Lincoln suspended, but did not commute, the death sentences of all but 38 condemned Dakota soldiers. On December 26, 1862, the 38 lost their lives in the largest mass hanging in U.S. history. Federal troops transported the spared Dakota soldiers out of state. When Moses Many Lightning Face, imprisoned near Davenport, Iowa, learned of Lincoln’s assassination, he wondered what would happen next.

Johannes Oertel

Johannes Oertel lived an eclectic life. Born in Bavaria (now part of Germany), he immigrated to the United States in 1848. He worked as an artist and became an Episcopal minister in 1867. His 1865 diary demonstrates his religiosity.

Mary Sheehan Ronan

As a child, Mary Sheehan settled in Virginia City, Montana, with her family. That mining boomtown had originally been named Varina, for the wife of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, because of the strong Confederate sympathies of its inhabitants. So it is perhaps not a surprise that Sheehan reported dancing among children as they learned of Lincoln’s assassination.

Emilie Davis

A free African-American woman in Philadelphia, Davis recorded her experiences in a diary between 1863 and 1865. This diary is a valuable resource for understanding the lives of free African Americans in the North during this time. Davis’s recollections of the Lincoln funeral in Philadelphia tell of both official and unofficial events.

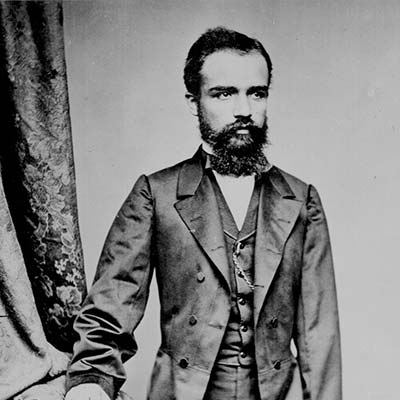

Matias Romero

Matias Romero represented Mexico’s Liberal government in the United States, seeking aid for his cause’s fight against Mexican monarchists supported by French invaders. Romero’s letters to Mexico’s leaders show his expectations for the course of U.S. policy toward his country under President Andrew Johnson.

Dudley Avery

The Avery family owned Petite Anse Island plantation in southwestern Louisiana, which included a salt mine. Dudley Avery, son of plantation owner Daniel D. Avery, served as a soldier in the Confederate Army. He eventually returned to the family's plantation, where he was when he learned of the Lincoln assassination. In a letter to his father, Dudley Avery feared that President Andrew Johnson would take a harsh stance toward former rebels, and expressed his belief in Lincoln’s magnanimity. Avery’s brother-in-law later developed Tabasco sauce at the plantation.

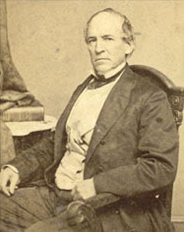

Horatio Nelson Taft

A U.S. Patent Office examiner, Taft kept a diary during his time living in Washington during the Civil War. His son, Charles Sabin Taft, was among the doctors who attended the wounded president. Taft’s diary provides one of the most compelling firsthand accounts of the scene in Washington after the assassination.

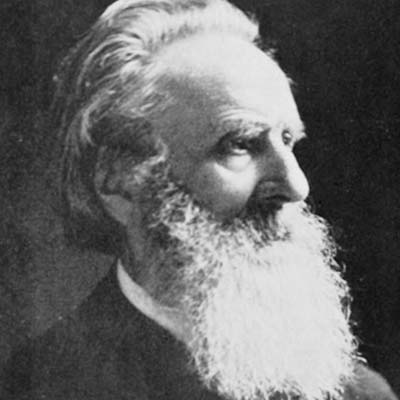

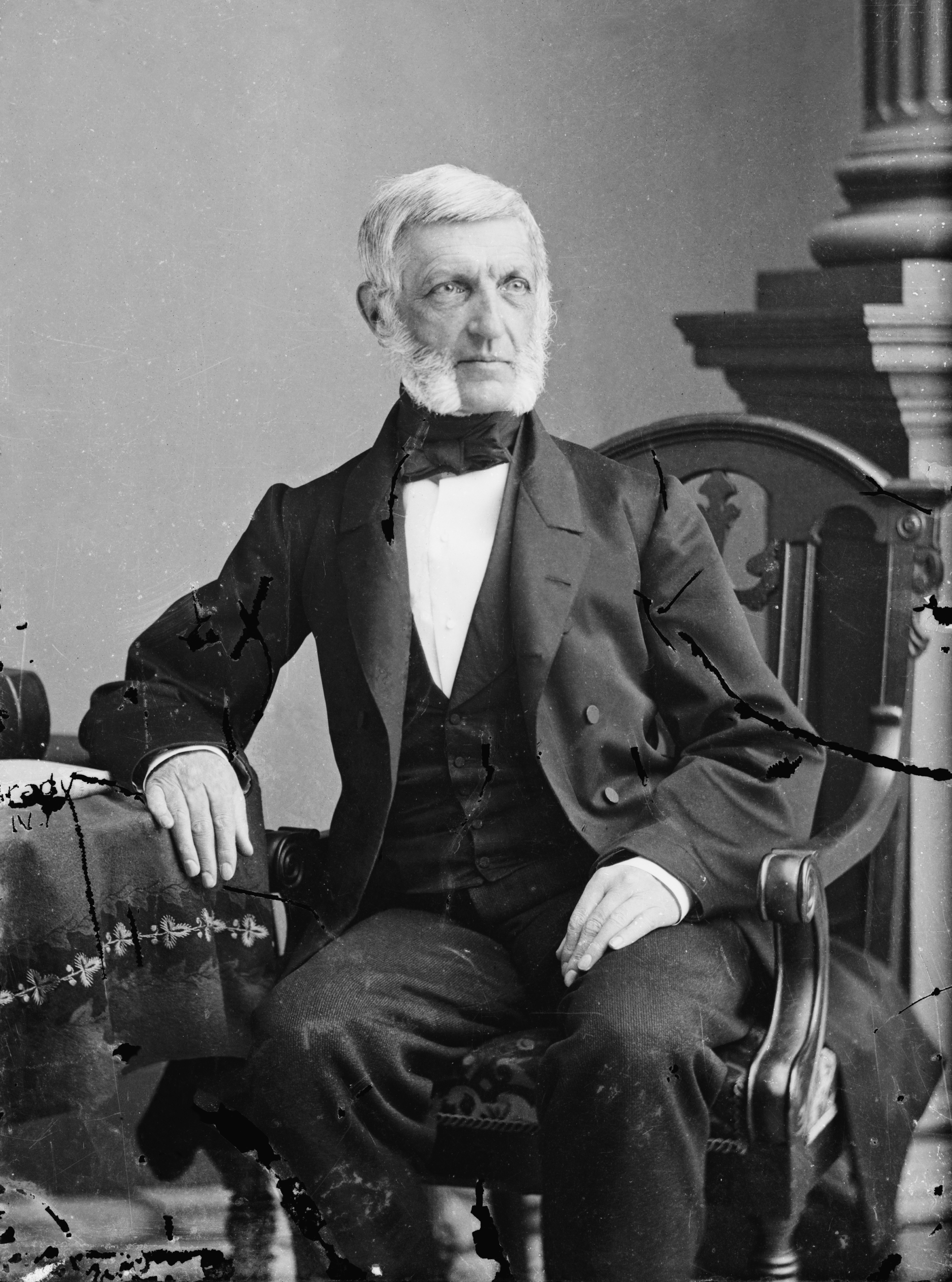

George Bancroft

An American historian and statesman, George Bancroft is best known for creating the United States Naval Academy while serving as Secretary of the Navy under President James K. Polk. He also wrote several historical works. In 1866, Congress asked Bancroft to deliver a eulogy in honor of Abraham Lincoln. Not everyone liked it.

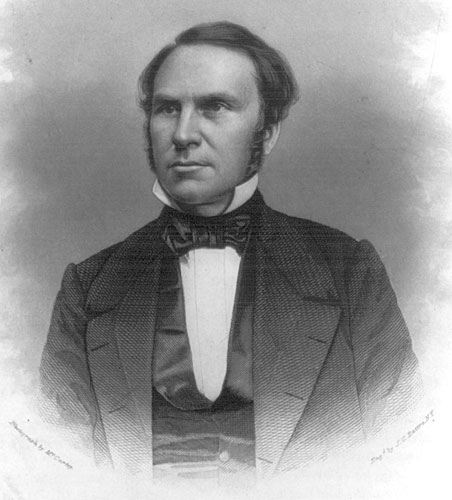

Dr. Phineas D. Gurley

Dr. Phineas D. Gurley was pastor of New York Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C. and Chaplain of the United States Senate during presidency of Abraham Lincoln. President Lincoln and First Lady Mary Lincoln regularly attended the church. Dr. Gurley was present at Lincoln’s deathbed and preached the funeral sermon at the White House on April 19, 1865.

Abigail M. Brooks

Abigail M. Brook (also known as Abbie Lindley) was a rural Tennessee school teacher in the 1860s. During the Civil War, she taught in a one room schoolhouse and made money on the side by selling religious texts, maps, and Civil War photos. Her 1865 diary provides detailed descriptions of rural life, the fall of Richmond, General Lee’s surrender, and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

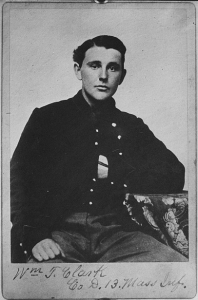

Willie Clark

Willie Clark was a boarder at the Petersen Boarding House in April 1865. He was out the night of April 14, making his bed available for the dying President Lincoln. Clark’s letter to his sister describes Lincoln’s funeral preparations and the constant influx of souvenir hunters into his room.

Clara Barton

Clara Barton is best known for founding the Red Cross. During the Civil War, she was the director of the Missing Soldiers Office. The Missing Soldiers Office, just three blocks from Ford’s Theatre in downtown Washington, D.C., helped families get information on their loved ones. Barton recorded the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and his funeral in her diary.

Queen Victoria

Queen Victoria was British monarch from 1837 until 1901. In 1861, Victoria went into deep mourning after her husband Prince Albert died. In a letter to First Lady Mary Lincoln, Victoria expressed the connection she felt after they both lost their husbands. Though the women never met, they shared a brief correspondence.

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony is best known as a women’s rights activist and suffragette. During the 1860s, she was heavily involved in the anti-slavery movement. She helped start the Women’s Loyal National League in 1863 which advocated for the abolition of slavery. She wrote about Lincoln’s assassination in a diary she kept during the Civil War.

Charles Frances Adams

The son and grandson of presidents, Charles Francis Adams served as the United States Minister to the United Kingdom under President Abraham Lincoln. He was instrumental in keeping Great Britain neutral during the U.S. Civil War. Adams received and wrote many dispatches to Secretary of War Stanton and acting Secretary of State William Hunter about Lincoln’s assassination and funeral.

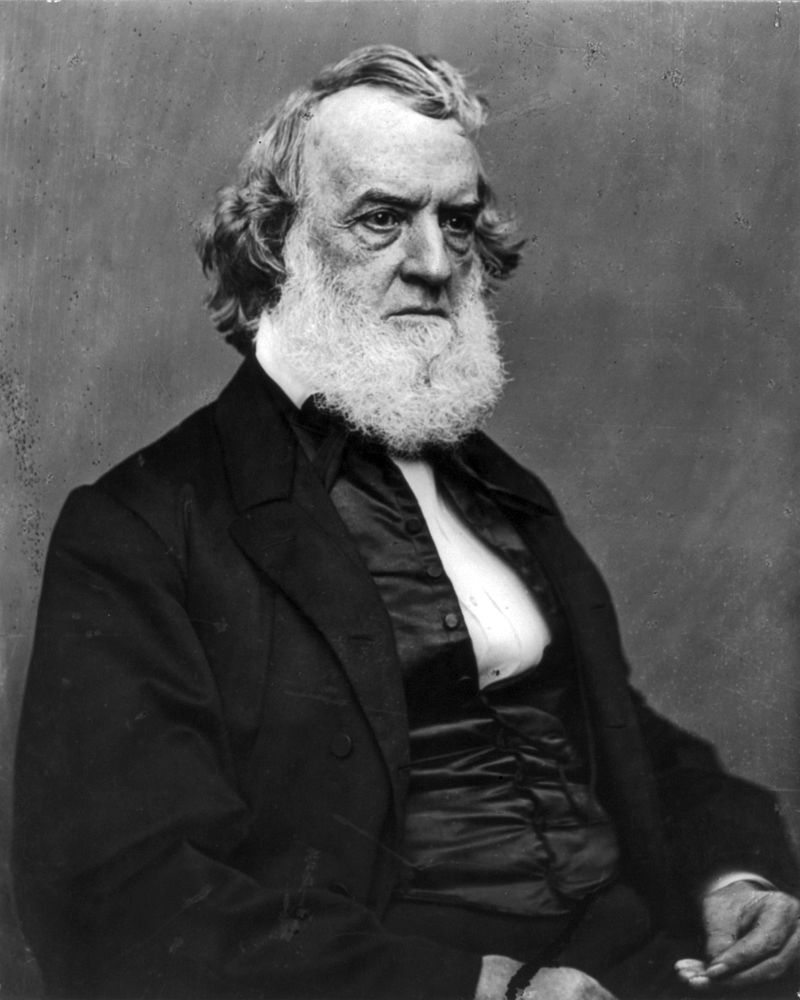

Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles was Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869 under Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson. After retiring from politics, he wrote Lincoln and Seward in 1874. Many telegrams to and from Welles appear in Remembering Lincoln, detailing the assassination of Lincoln and the manhunt for John Wilkes Booth.

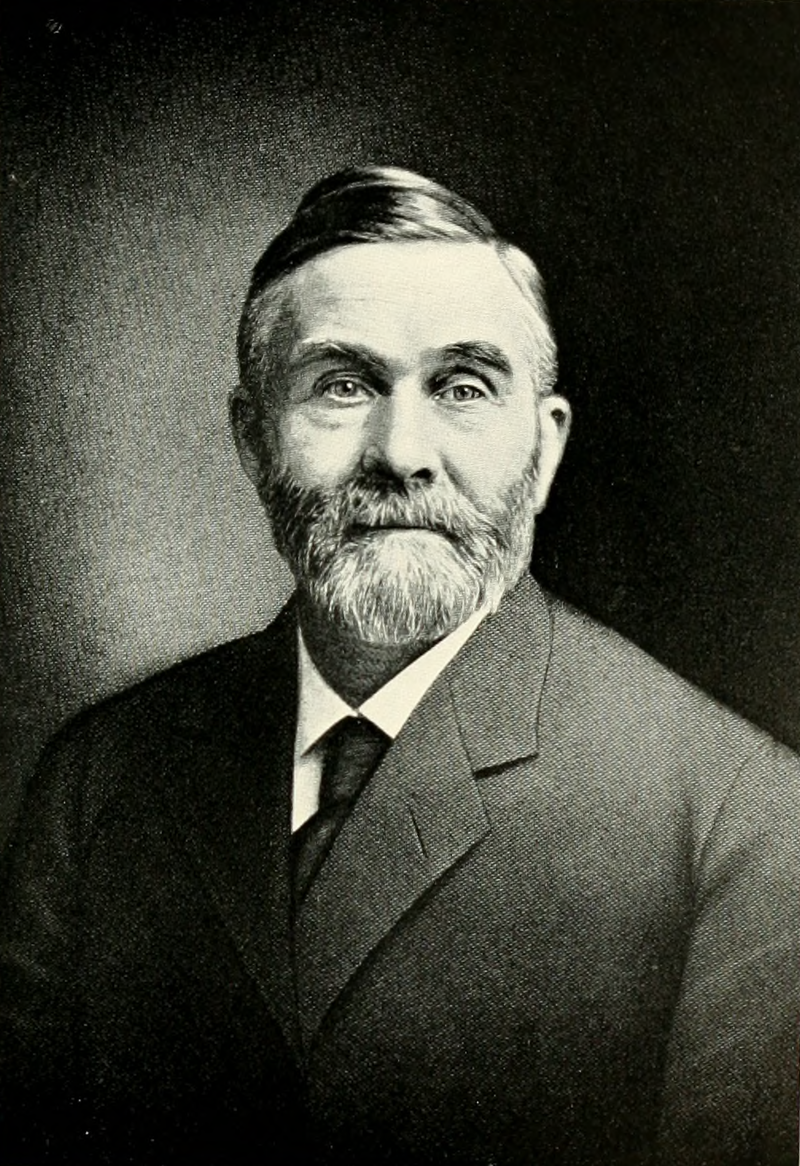

George Himes

George Himes lived in Portland, Oregon, working as a printer and journalist throughout his life. From the age of 14 until his death at 95, Himes kept a constant journal of his daily activities. In 1865, Himes recorded his reaction to the Lincoln assassination and the process of creating a special edition newspaper about the event. He eventually helped found the Oregon Historical Society.