from Apr. 23, 1865

The Lesson of President Lincoln's Death

-

Full Title

The Lesson of President Lincoln's Death: A Speech of Wendell Phillips at the Tremont Temple, on Sunday Evening, April 23, 1865

-

Description

Abolitionist Wendell Phillips delivered this speech at Tremont Temple baptist church in Boston in the days after the Lincoln assassination. Phillips calls for African American rights as part of Lincoln's legacy.

-

Transcription

THE LESSON OF PRESIDENT LINCOLN’S DEATH: A SPEECH OF WENDELL PHILLIPS,

At the Tremont Temple, on Sunday Evening, April 23, 1865.

These are sober days. The judgments of God have found us out. Years gone by chastised us with whips; these chastise us with scorpions. Thirty years ago, how strong our mountain stood, laughing prosperity on all its sides! None heeded the fire and gloom which slumbered below. It was nothing that a giant sin gagged our pulpits; that its mobs ruled our streets, burnt men at the stake for their opinions, and hunted them like wild beasts for their humanity. It was nothing, that, in the lonely quiet of the plantation, there fell on the unpitied person of the slave every tortue which hellish ingenuity could devise. It was nothing that as husband and father, mother, and child, the negro drained to its dregs all the bitterness that could be pressed into his cup; that, torn with whip and dogs, staved, hunted, tortured, racked, he cried, “How long! O Lord, how long!” In vain did a thousand witnesses crowd our highways, telling to the world the horrors of this prison-house. None stopped to consider, none believed. Trade turned away its deaf ear; the Church gazed on them with stony brow; Letters passed by with mocking tongue. But what the world would not look at, God has set to-day in a light so ghastly bright, that it almost dazzles us blind. What the world refused to believe, God has written all over in the face of the continent, with the sword’s point, in the blood of our best and most beloved. We believe the agony of the slave’s hovel, the mother, and the husband, when it takes its seat at our board We realize the barbarism that crushed him in the sickening and brutal use of the relics of BUll RUn, in the torture and starvation of Libby Prison, where idiocy was mercy, and death was God’s best blessing; and now, still more bitterly, we must it in the coward spite which strikes an unarmed man, unwarned, behind his back; in the assassin fingers which dabble with bloody knite at the throats of old men on sick pillows. O, God! Let this lesson be enough! Spare us any more such costly teaching!

This deed is but the result, and fair representative, of the system in whose defence it was done. No matter whether it was previously approved at Richmond, or whether the assassin, if he reaches the confederates, be received with all honor, as the wretch Brooks was, and as this bloodier wretch will surely be, wherever rebels are not dumb with fear of our cannon. No matter for all this. God shows this terrible act to teach the nation, in unmistakable terms, the terrible foe with which it has to deal. But for this fiendish spirit, North and South, which holds up the rebellion, the assassin had never either wished or dared such a deed. This lurid flash only shows us how black and wide the cloud from which it sprung.

And what of him in whose precious blood this momentous lesson is writ? He sleeps in the blessings of the poor, whose fetters God commissioned him to break. Give prayers and tears to the desolate widow and the fatherless; but count him blessed far above the crowd of his fellow-men. [Fervent cries of “Amen!”] He was permitted himself to deal the last staggering blow which sent rebellion reeling to its grave; and then, holding his darling boy by the hand, to walk the streets of its surrendered capital, while his ears drank in praise and thanksgiving which bore his name to the throne of God in every form piety and gratitude could invent; and finally, to steal the sure triumph of the cause he loved with his own blood. He caught the first notes of the coming jubilee, and heard his own name in every one. Suppose that, when a boy, as he floated on the slow current of the Mississippi, idly gazing at the slave upon its banks, some angel had lifted the curtain, and shown him, that, in the prime of his manhood, he should see this proud empire rocked to its foundation in the effort to break those chains; should himself marshal the hosts of the Almighty in the grandest and holiest war that Christendom ever knew, and deal, with half-reluctant hand, that thunderbolt of justice which would smite the foul system to the dust; then die, leaving a name immortal in the study pride of our race and the undying gratitude of another, — would any credulity, however sanguine, any enthusiasm, however fervid, have enabled him to believe it? Fortunate man! He has lived todo it! [Applause.] God has graciously withheld him from any fatal misstep in the great advance, and withdrawn him at the moment which his star touched its zenith, and the nation needed a sterner hand for the work God gives it to do.

No matter now, that, unable to lead and form the nation, he was contented to be only its representative and mouthpiece; no matter, that, with prejudices hanging about him, he groped his way very slowly and sometimes reluctantly forward; let us remember how patient he was of contradiction, how little obstinate in opinion, how willing, like Lord Bacon, “to light his torch at every man’s candle.” With the least possible personal hatred; with too little sectional bitterness, often forgetting justice in mercy; tender-hearted to any misery his own eyes saw; and in any deed which needed his actual sanction, if his sympathy had limits, recollect he was human, and that he welcomed light more than most men, was more honest than his fellows, and with a truth to his own convictions such as few politicians achieve. With all his shortcomings, we point proundly to him as the natural growth of democratic institutions. [Applause.] Coming time will put him in that galaxy of Americans which makes our history the day-star of the nations, — Washington, Hamilton, Franklin, Jefferson and Jay. History will add his name to the bright list, with a more loving claim on our gratitude than either of them. No one of those was called to die for his cause. For him, when the nation needed to be raised to its last dread duty, we were prepared for it by the baptism of his blood.

What shall we say as to the punishment of rebels? The air is thick with threats of vengeance. I admire the motive which prompts these; but let us remember, no cause, however infamous, was ever crushed by punishing its advocates and abettors. All history proves this. There is no class of men base and coward enough, no matter what their view and purpose, to make the policy of vengeance successful. In bad causes, as well as good, it is still true that “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.” We cannot prevail against this principle of human nature. And, again, with regard to the dozen chief rebels, it will never be a practical question whether we shall hang them. Those not now in Europe will soon be there. Indeed, after paroling the bloodiest and guiltiest of all, Robert Lee [loud applause], there would be little fitness in hanging any lesser wretch.

The only punishment which ever crushes a cause is that which its leaders necessarily suffer in consequence of the new order of things made necessary to prevent the recurrence of their sin. It was not the blood of two peers and thirty commoners, which England shead after the rebellion of 1715, or that of five peers and twenty commoners, after the rising of 1745, which crushed the House of Stuart. Though the fight had lasted only a few months, those blocks and gibbets gave Charles his only change to recover. Bute the confiscated lands of his adherents, and the new political arrangement of the Highlands, — just, and recognized as such, because necessary, — these quenched his star forever.

Our Rebellion has lasted four years. Government has exchanged prisoners and acknowledged its belligerent rights. After that, gibbets are out of the question. A thousand men rule the Rebellion, — are the Rebellion. A thousand men! We cannot hang them all. We cannot hang men in regiments. What, over the continent with gibbets! We cannot sichen the nineteenth century with such a sight. It would sink our civilization to the level of Southern barbarism. It would forfeit our very right to supersede the Southern system, which right is based on ours being better than theirs. To make its corner-stone the gibbet would degrade us to the level of Davis and Lee. The structure of Government which bore the earthquake shock of 1861 with hardly a jar, and which now bears the assassination of its Chief Magistrate, in this crisis of civil war, with even less disturbance, needs, for its safety, no such policy of vengeance; its serene strength needs to use only so much severity as will fully guarantee security for the future.

Banish every one of these thousand rebel leaders, — every one of them, on pain of death if they every return! [Loud applause.] Confiscate every dollar and acre they own. [Applause.] These steps the world and their followers will see are necessary to kill the seeds of caste, dangerous State rights and secession. [Applause.] Banish Lee with the rest. [Applause.] No Government should ask of the South which he has wasted and the North which he has murdered such superabundant Christian patience as to tolerate in our streets the presence of a wretch whose hand upheld Libby Prison and Andersonville, and whose soul is black with sixty-four thousand deaths of prisoners by starvation and torture.

What of our new President? His whole life is a pledge that he knows and hates thoroughly that caste which is the Gibraltar of secession. Caste, mailed in States rights, seized slavery as its weapon to smite down the Union. Said Jackson, in 1833; “Slavery will be the next pretext for rebellion.” PRETEXT! That pretext and weapon we wrench from the rebel hands the moment we pass the anti-slavery amendment to the Constitution. Now kill caste, the foe who wields it. Andy Johnson is our natural leader for this. His life has been pledged to it. He put on his spurs with this vow of knighthood. He sees that confiscation, land placed in the hands of the masses, is the means to kill this foe.

Land and the ballot are the true foundations of all Governments. Intrust them wherever loyalty exists, to all those, black and white, who have upheld the flag. [Applause.] Reconstruct no State without giving to every loyal man in it the ballot. I scout all limitations of knowledge, property or race. [Applause.] Universal suffrage for me. That was the Revolutionary model. Every freeman voted, black or white, whether he could read or not. My rule is, any citizen liable to be hanged for crime is entitled to vote for rulers. The ballot insures the school.

Mr. Johnson has not yet uttered a word which shows that he sees the need of negro suffrage to guarantee the Union. The best thing he has said on this point, showing a mind open to light, is thus reported by one of the most intelligent men in the country, the Baltimore correspondent of the Boston Commonwealth: —

“The Vice-President was holding forth very eloquently in front of Admiral Lee’s dwelling, just in front of the War-Office in Washington. He said he was willing to send every negro in the countray to Africa to save the Union. Nay, he was willing to cut Africa loose from Asia, and sink the whole black rae ten thousand fathoms deep to effect this object. A loud voice sang out in the crowd, ‘Let the negro stay where he is, governor, and give him the ballot, and the Union will be safe forever!’ ‘And I am ready to do that, too!’ [loud applause] shouted the governor, with intense energy, whereat he got three times three for the noble sentiment. I witnessed this scene, and was pleased to hear that our Vice-President take this high ground, for up to this point must the nation quickly advance, or there will be no peace, no rest, no prosperity, no blessing, for our suffering and distracted country.”

The need of giving the negro a ballot is what we must press on the President’s attention. Beware the mistake which fastened McClellan on us, running too fast to indorse a man while untried, determined to manufacture a hero and leader at any rate. The President tells us that he waits to announce his policy till events call for it, — a wise, timely, and statesman-like course. Let us imitate it. Assure his in return that the government shall have our support like good citizens. But remind him that we will think him what we think of his poliey when we learn what it is. He says, “Wait: I shall punish; I shall confiscate. What more I shall do, you will know when I do it.”

Let us reply: “Good! So far, good! Banish the rebels. See to it that, beyond all mistake, you strip them of all possibility of doing harm. But see to it also that before you admit a single State to the Union, you oblige it to give every loyal man in it the ballot, — the ballot, which secures education; the ballot, which begets character where it lodges responsibility; the ballot, having which, no class need fear injustice or contempt; the ballot, which puts the helm of the Union into the hands of these who love and have upheld it. Land, — where every man’s title-deed, based on confiscation, is the bond which ties his interest to the Union; ballot, — the weapon which enables him to defend his property and the Union. These are the motives for the white man: the negro needs no motive but his instinct and heart. Give him the bullet nad ballot, he needs them; and while he holds them the Union is safe. To reconstruct now without giving the negro the ballot would be a greater blunder, and considering our better light, a greater sin that our fathers committed in 1789; and we should have no right to expect from it any less disastrous results.”

This is the lesson God teaches us in the blood of Lincoln. Like Egypt, we are made to read our lesson in the blood of our first-born, and the seats of our princes left empty. We bury all false magnanimity in this fresh grave, writing over it the maxim of the coming four years: “Treason is the greatest of crimes, and not a mere difference of opinion.” That is the motto of our leader to-day, — that the warning this atrocious crime sounds throughout the land. Let us heed it, and need no more such costly teaching. [Loud applause.]

[Transcription by: Hannah A.B., Dr. Susan Corbesero’s Class, Ellis School, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania]

-

Source

Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection via The Internet Archive

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Wendell Phillips. "The Lesson of President Lincoln's Death: A Speech of Wendell Phillips at the Tremont Temple, on Sunday Evening, April 23, 1865". Press of Geo. C. Rand & Avery. Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1195

-

Creator

Wendell Phillips

-

Publisher

Press of Geo. C. Rand & Avery

-

Date

April 23, 1865

from Apr. 23, 1865

The Lesson of President Lincoln's Death: A Speech of Wendell Phillips at the Tremont Temple, on Sunday Evening, April 23, 1865

-

Description

Abolitionist Wendell Phillips delivered this speech at Tremont Temple baptist church in Boston in the days after the Lincoln assassination. Phillips calls for African American rights as part of Lincoln's legacy.

-

Source

Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection via The Internet Archive

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Wendell Phillips

-

Publisher

Press of Geo. C. Rand & Avery

-

Date

April 23, 1865

from Apr. 22, 1865

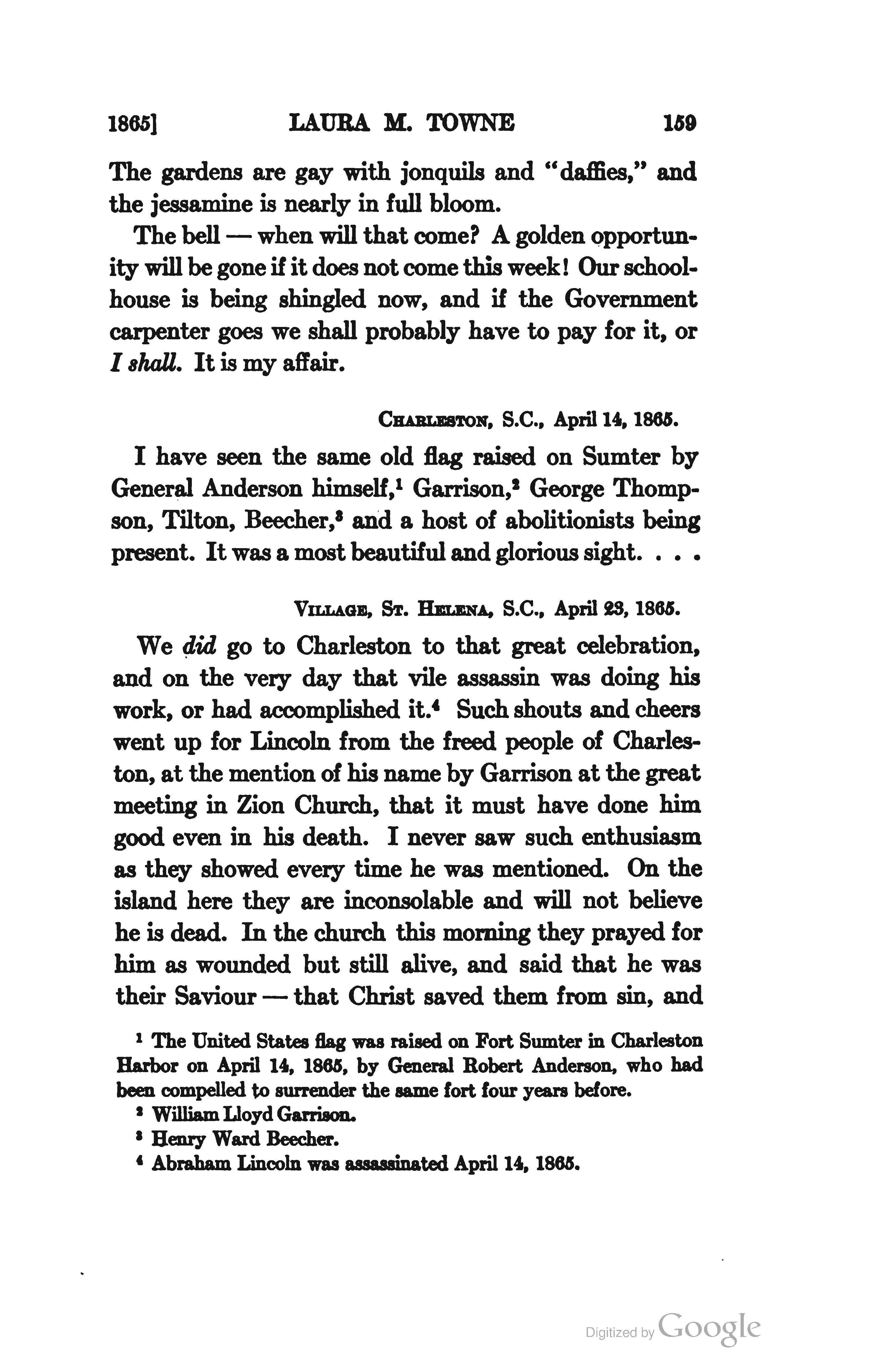

Excerpts from the Letters and diary of Laura M. Towne

-

Full Title

Excerpts from the Letters and diary of Laura M. Towne

-

Description

Laura M. Towne was an abolitionist and an educator. Before the Civil War, Towne was studying medicine but was motivated to become an abolitionist after the outbreak of the Civil War. Towne volunteered when the Union captured Port Royal and other Sea Islands area of South Carolina. She and her friend, Ellen Murray, founded the Penn Center on St. Helena Island, the first school for freed slaves. Her diaries and letters from this time were edited by Rupert Sargent Holland and published in 1912.

-

Transcription

The gardens are gay with jonquils and “daffies,” and the jessamine is nearly in full bloom.

The bell — when will that come? A golden opportunity will be gone if it does not come this week! Our schoolhouse is being shingled now, and if the Government carpenter goes we shall probably have to pay for it, or I shall. It is my affair.

Charleston, S.C., April 14, 1865.

I have seen the same old flag raised on Sumter by General Anderson himself,1 Garrison,2 George Thompson, Tilton, Beecher,3 and a host of abolitionists being present. It was a most beautiful and glorious sight…

Village, St. Helena, S.C., April 23, 1865.

We did go to Charleston to that great celebration, and on the very day that vile assassin was doing his work, or had accomplished it.4 Such shouts and cheers went up for Lincoln from the freed people of Charleston, at the mention of his name by Garrison at the great meeting in Zion Church, that it must have done him good even in his death. I never saw such enthusiasm as they showed every time he was mentioned. On the island here they are inconsolable and will not believe he is dead. In the church this morning they prayed for him as wounded but still alive, and said that he was their Saviour — that Christ saved them from sin, and

1. The United States flag was raised on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 14, 1865, by General Robert Anderson, who had been compelled to surrender the same fort four years before.

2. Willian Lloyd Garrison.

3. Henry Ward Beecher.

4. Abraham Lincoln was assassinated April 14, 1865.

----------------------------------

he from “Secesh,” and as for the vile Judas who had lifted his hand against him, they prayed the Lord the whirlwind would carry him away, and that he would melt as wax in the fervent heat, and be driven forever from before the Lord. Was n’t it the cunning of the Devil that did the deed; and they are going to prove him insane! When he was wise enough to strike the one in whom all could trust, and whose death would inevitably throw confusion and doubt into the popular mind of the North! And then to single out Seward2 in hopes that the next Secretary might embroil us with Europe and so give them another chance! It is so hard to wait a week or two before we know what comes next.

But I must tell you of our trip to Charleston. General Saxton gave us all passes, and a large party of teachers went from this island with Mr. Ruggles — good, kind, handsome fellow — to escort us. We stayed at a house kept by the former servants or slaves of Governor Aiken.

I was dreadfully seasick going up, and the day after I got there had to go to bed, and so I missed seeing many things I should have liked to visit. It stood — the house we stayed at —in the very heart of the shelled part of the city, and had ever so many balls through it. The burnt part of the town is the picture of desolation, and the detested “old sugar-house,” as the workhouse was called, looks like a giant in his lair. It was where all the slaves were whipped, and the whipping-room was made with double walls filled in with sand so that the cries could not be heard in the street. The treadmill and all

2 An attempt was also made to assassinate Secretary State Seward.

--------------------------------------------

kinds of tortures were inflicted there. I wanted to make sure of the building and asked an old black woman in that was the old sugar-house. “Dat’s it,” she said, “but it’s all played out now.” On Friday we went to Sumter, got good seats in the amphitheatre inside, near the pavilion for the speakers, and had a good opportunity to see all. I think there was not that enthusiasm in Anderson that I expected, and Henry Ward Beecher addressed himself to the “citizens of Charleston,” when there were not a dozen there. He spoke very much by note, and quite without fire.

At Sumter I bought several photographs, and send you one of the face [of the fortress] farthest from Wagner, Gregg, and our assailing forts, and consequently pretty well preserved. If you look closely you will see rows of basket-work, filled with sand, repairing a break. The whole inside of the fort is lined with them.

The next day was the grand day, however, when Wilson, Garrison, Thompson, Kelly, Tilton, and others spoke. Redpath mentioned John Brown’s name, and asked the great congregation to sing his favorite hymn, “Blow ye the Trumpet,” or “Year of Jubilee.”

I spoke to Judge Kelly afterwards and had a nice promise from him that he would send me all his speeches. We came home on Sunday and found all the missing boxes arrived,— or nearly all,— among them, mine. You do not know how intensely we all enjoy your picture—that exquisite sea-view. How could you spare me such a picture! I lie down on our sofa which faces it, and do so heartily enter into the freshness of it that it is refreshing in this hot weather. Many thanks to you.

------------------------------------------------

[The next letter refers to the death of President Lincoln.]

Saturday, April 29, 1865.

… It was a frightful blow at first. The people have refused to believe he was dead. Last Sunday the black minister of Frogmore said that if they knew the President were dead they would mourn for him, but they could not think that was the truth, and they would wait and see. We are going to-morrow to hear what further they say. One man came for clothing and seemed very indifferent about them — different from most of the people. I expressed some surprise. “Oh,” he said, “I have lost a friend. I don’t care much now about anything.” “What friend?” I asked, not really thinking for a moment. “They call him Sam,” he said; “Uncle Sam, the best friend ever I had.” Another asked me in a whisper if it were true that the “Government was dead.” Rina says she can’t sleep for thinking how sorry she is to lose “Pa Linkum.” You know they call their elders in the church—of the particular one who converted and received them in — their spiritual father, and he has the most absolute power over them. These fathers are addressed with feat and awe as “Pa Marcus,” “Pa Demas,” etc. One man said to me, “Lincoln died for we, Christ died for we, and me believe him de same mans,” that is, they are the same person.

We dressed our school-house in what black we could get, and gave a shred of crape to same of our children, who wear it sacredly. Fanny’s bonnet supplied the whole school.

[Transcription by: Grace C., Dr. Susan Corbesero’s Class, Ellis School, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania] -

Source

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Laura M. Towne. "Excerpts from the Letters and diary of Laura M. Towne". Cambridge, Printed at the Riverside Press,. Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1194

-

Creator

Laura M. Towne

-

Publisher

Cambridge, Printed at the Riverside Press,

-

Date

April 22, 1865

from Apr. 22, 1865

Excerpts from the Letters and diary of Laura M. Towne

-

Description

Laura M. Towne was an abolitionist and an educator. Before the Civil War, Towne was studying medicine but was motivated to become an abolitionist after the outbreak of the Civil War. Towne volunteered when the Union captured Port Royal and other Sea Islands area of South Carolina. She and her friend, Ellen Murray, founded the Penn Center on St. Helena Island, the first school for freed slaves. Her diaries and letters from this time were edited by Rupert Sargent Holland and published in 1912.

-

Source

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Laura M. Towne

-

Publisher

Cambridge, Printed at the Riverside Press,

-

Date

April 22, 1865

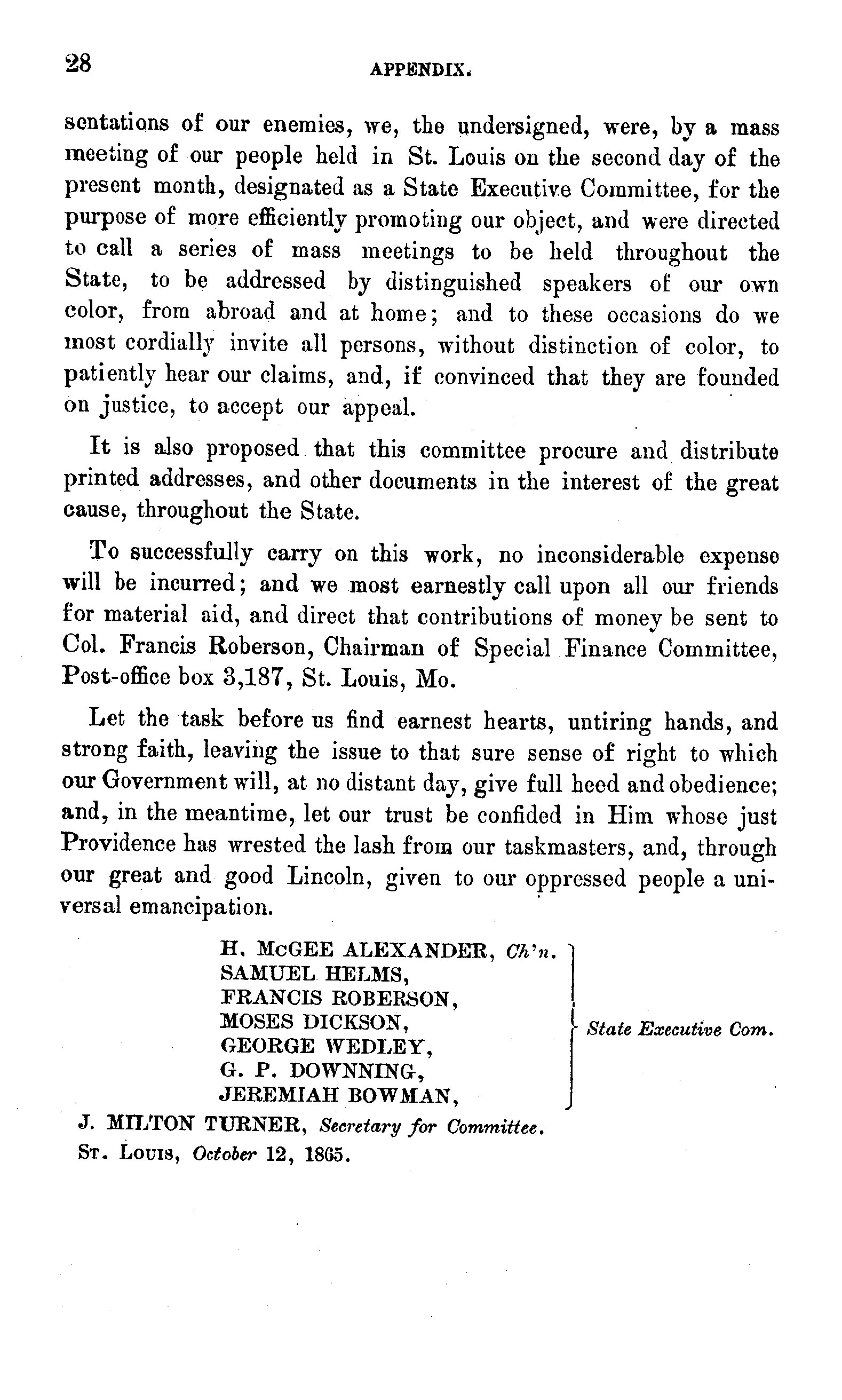

from Jan. 9, 1866

A Speech on "Equality Before the Law"

-

Full Title

A Speech on "Equality Before the Law" Delivered by J. Mercer Langston In the Hall of Representatives in the Capitol of Missouri

-

Description

In this pamphlet put together by the Missouri State Executive Committee, a speech delivered by John Mercer Langston on January 9th, 1866 called for political emancipation for African Americans. Also within this pamphlet, an address by the Colored People of Missouri to the Friends of Equal Rights strived to make manhood, not color, the basis of suffrage and thanked God for using President Lincoln to emancipate African American slaves.

-

Source

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Missouri State Executive Committee. "A Speech on "Equality Before the Law" Delivered by J. Mercer Langston In the Hall of Representatives in the Capitol of Missouri". Democrat Book and Job Printing House. Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1129

-

Creator

Missouri State Executive Committee

-

Publisher

Democrat Book and Job Printing House

-

Date

January 9, 1866

from Jan. 9, 1866

A Speech on "Equality Before the Law" Delivered by J. Mercer Langston In the Hall of Representatives in the Capitol of Missouri

-

Description

In this pamphlet put together by the Missouri State Executive Committee, a speech delivered by John Mercer Langston on January 9th, 1866 called for political emancipation for African Americans. Also within this pamphlet, an address by the Colored People of Missouri to the Friends of Equal Rights strived to make manhood, not color, the basis of suffrage and thanked God for using President Lincoln to emancipate African American slaves.

-

Source

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Missouri State Executive Committee

-

Publisher

Democrat Book and Job Printing House

-

Date

January 9, 1866

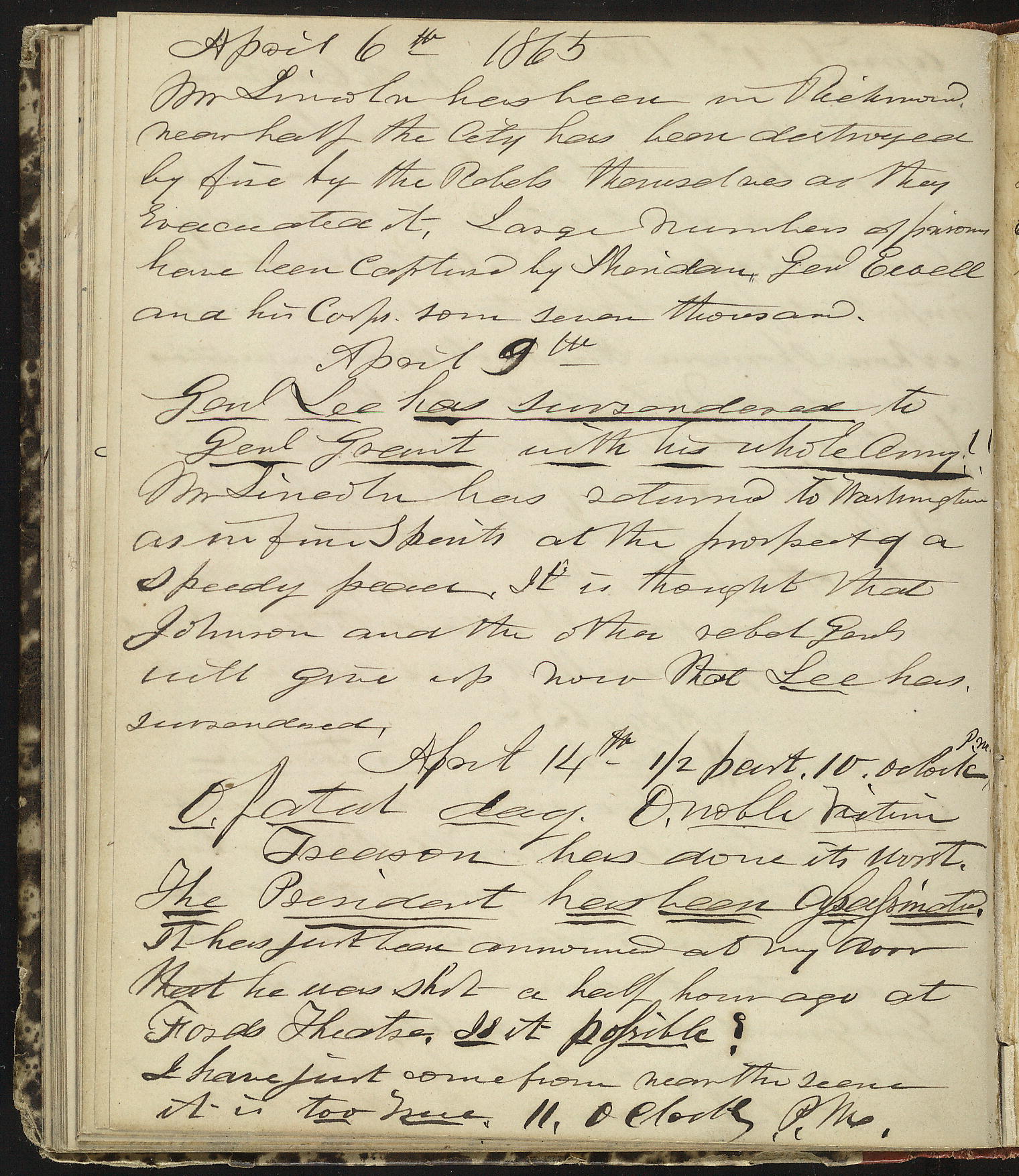

from Apr. 14, 1865

Horatio Nelson Taft Diary, April 6-14, 1865

-

Full Title

Horatio Nelson Taft Diary, April 6-14, 1865

-

Description

This excerpt from the diary of Horatio Nelson Taft is an insight into some of the first reactions of citizens of the Union to the death of President Lincoln. Taft, who was a patent clerk, laments Lincoln's teach and denounces the assassination as assassination at it's worst. In the entry just prior to the excerpt describing Lincoln's death, Taft described the return of Lincoln to Washington after a Union victory.

-

Transcription

April 6th 1865

Mr Lincoln has been in Richmond. Near half of the City has been destroyed by fire by the

Rebels themselves as they evacuated it. Large numbers of prisoners have been captured

by Sheridan, Genl Ewell and his Corps, some seven thousand.

April 9, 1865

Genl Lee has surrendered to Genl Grant with his whole Army!! Mr Lincoln has returned to

Washington as in fine Spirits at the prospect of a speedy peace. It is thought that Johnson

and the other rebel Genls will give up now that Lee has surrendered.

April 14th ½ past 10 o'clock P.M.

O, fatal day. O, noble Victim.

Treason has done its worst.

The President has been Assassinated.

It has just been announced at my door

that he was shot a half hour ago at Fords Theatre.

Is it possible?

I have just come from near the scene,

it is too True. 11, o'clock P.M. -

Source

memory.loc.gov

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Horatio Nelson Taft. "Horatio Nelson Taft Diary, April 6-14, 1865". Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1107

from Apr. 14, 1865

Horatio Nelson Taft Diary, April 6-14, 1865

-

Description

This excerpt from the diary of Horatio Nelson Taft is an insight into some of the first reactions of citizens of the Union to the death of President Lincoln. Taft, who was a patent clerk, laments Lincoln's teach and denounces the assassination as assassination at it's worst. In the entry just prior to the excerpt describing Lincoln's death, Taft described the return of Lincoln to Washington after a Union victory.

-

Source

memory.loc.gov

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Horatio Nelson Taft

-

Date

April 14, 1865

-

Material

bound paper with script in ink and type

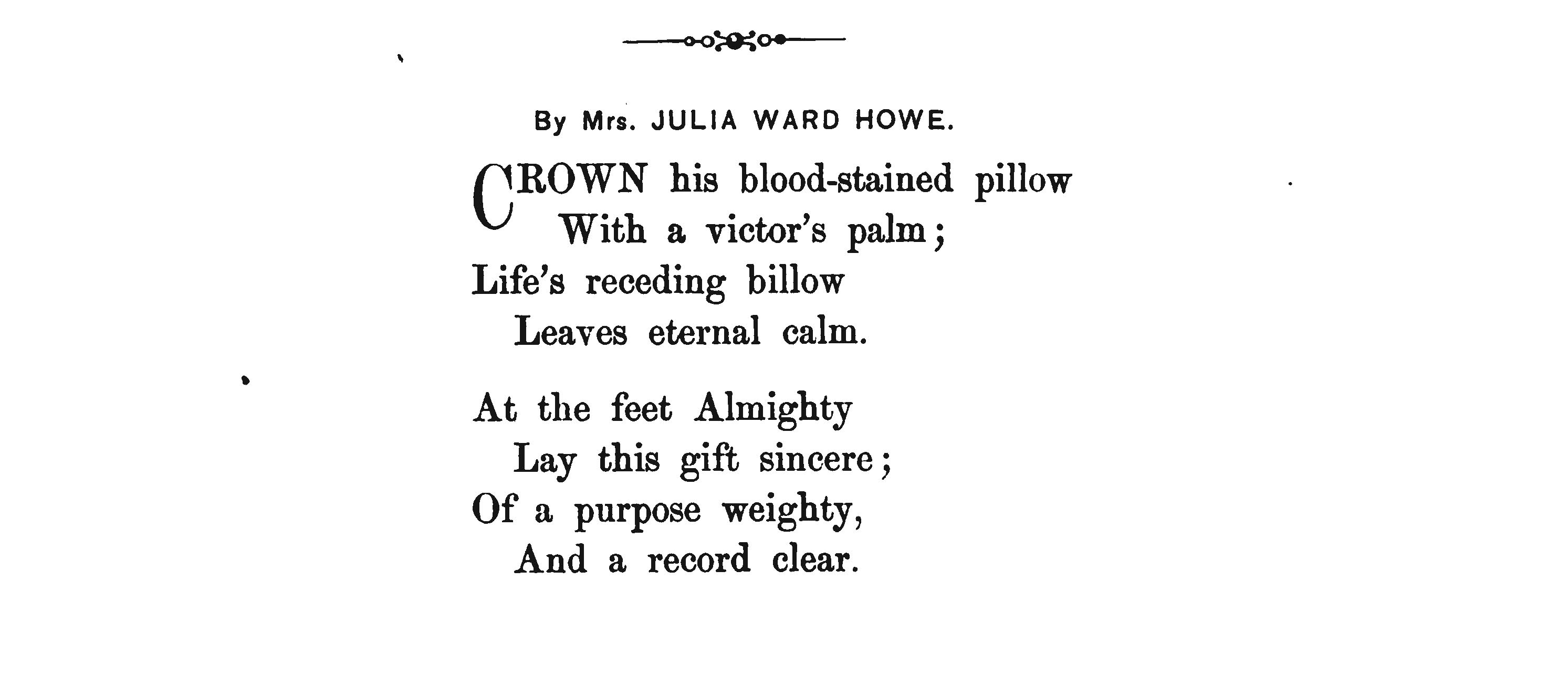

from Jul. 1, 1865

Julia Ward Howe Poem

-

Full Title

Poetical Tribute to President Lincoln - Julia Ward Howe

-

Description

Philadelphia publishing house J.B. Lippincott & Co. compiled poetical tributes to President Lincoln in the months after his assassination. This piece, by Julia Ward Howe, talks about Lincoln's legacy and how to honor him and his contributions to the nation. Julia Ward Howe was an abolitionist, suffragette and author, most famous for writing "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," which is now one of the most famous songs of the Civil War. She was inspired to write the song after meeting with President Lincoln at the White House in November 1861.

-

Source

University of Wisconsin - Madison, Digitized by Google

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Julia Ward Howe. "Poetical Tribute to President Lincoln - Julia Ward Howe". J.B. Lippincott & Co.. Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1100

-

Creator

Julia Ward Howe

-

Publisher

J.B. Lippincott & Co.

-

Date

1865

from Jul. 1, 1865

Poetical Tribute to President Lincoln - Julia Ward Howe

-

Description

Philadelphia publishing house J.B. Lippincott & Co. compiled poetical tributes to President Lincoln in the months after his assassination. This piece, by Julia Ward Howe, talks about Lincoln's legacy and how to honor him and his contributions to the nation. Julia Ward Howe was an abolitionist, suffragette and author, most famous for writing "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," which is now one of the most famous songs of the Civil War. She was inspired to write the song after meeting with President Lincoln at the White House in November 1861.

-

Source

University of Wisconsin - Madison, Digitized by Google

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Julia Ward Howe

-

Publisher

J.B. Lippincott & Co.

-

Date

July 1, 1865

from Jul. 1, 1865

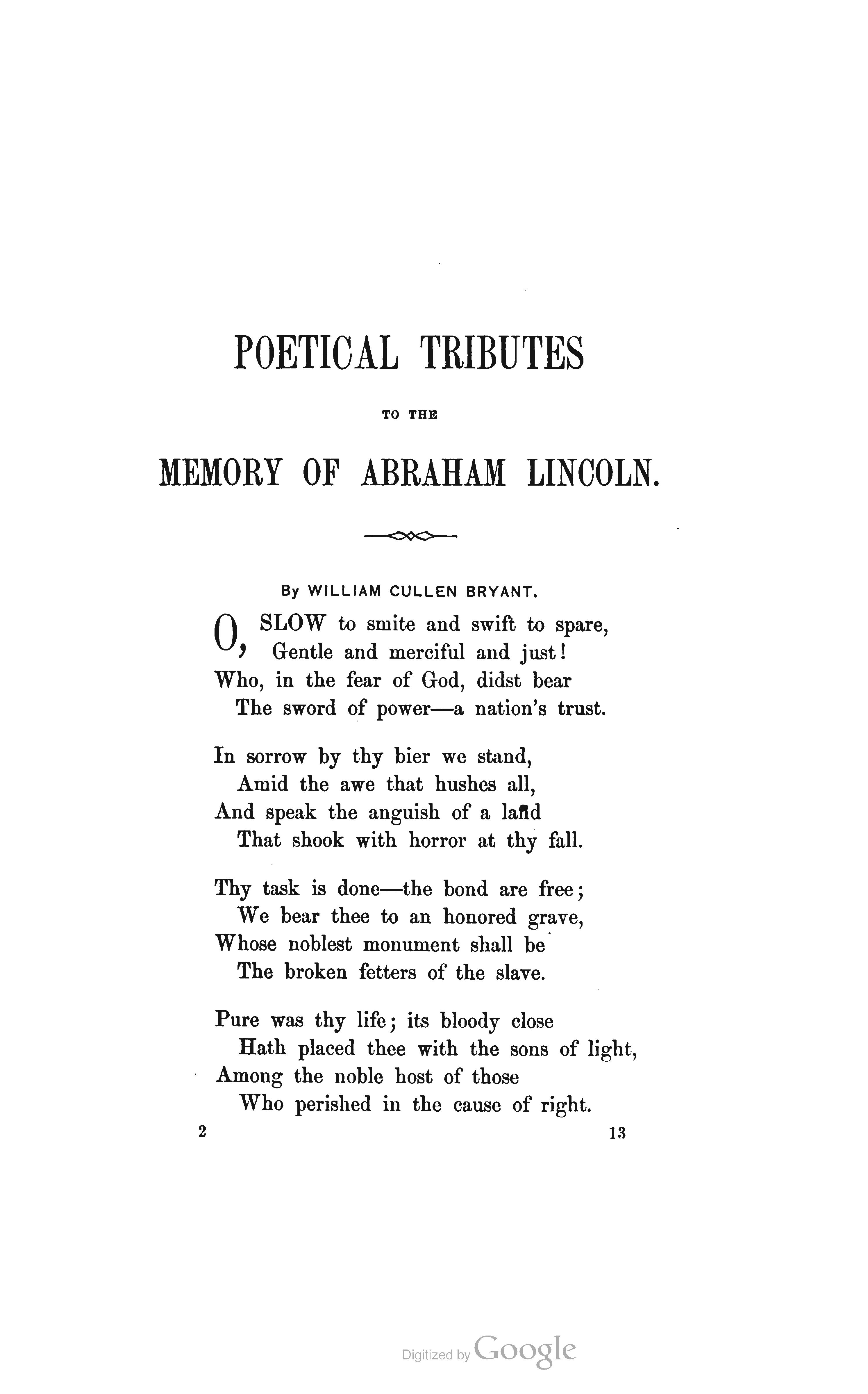

William Cullen Bryant Poem

-

Full Title

Poetical Tribute to President Lincoln - William Cullen Bryant

-

Description

Philadelphia publishing house J.B. Lippincott & Co. compiled poetical tributes to President Lincoln in the months after his assassination. This piece, by Poet William Cullen Bryant, speaks of Lincoln's life and greatest accomplishment, freeing the slave. Bryant was considered a child-prodigy, publishing his first poem at age ten and his first book when he was thirteen. He later served as editor for the New York Evening Post. He was a member of the Republican Party and actually introduced Abraham Lincoln at Cooper Union in New York when Lincoln gave his famed "Cooper Union Speech" in 1860.

-

Source

University of Wisconsin - Madison, Digitized by Google

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

William Cullen Bryant. "Poetical Tribute to President Lincoln - William Cullen Bryant". J. B. Lippincott & Co.. Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/1099

-

Creator

William Cullen Bryant

-

Publisher

J. B. Lippincott & Co.

-

Date

1865

from Jul. 1, 1865

Poetical Tribute to President Lincoln - William Cullen Bryant

-

Description

Philadelphia publishing house J.B. Lippincott & Co. compiled poetical tributes to President Lincoln in the months after his assassination. This piece, by Poet William Cullen Bryant, speaks of Lincoln's life and greatest accomplishment, freeing the slave. Bryant was considered a child-prodigy, publishing his first poem at age ten and his first book when he was thirteen. He later served as editor for the New York Evening Post. He was a member of the Republican Party and actually introduced Abraham Lincoln at Cooper Union in New York when Lincoln gave his famed "Cooper Union Speech" in 1860.

-

Source

University of Wisconsin - Madison, Digitized by Google

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

William Cullen Bryant

-

Publisher

J. B. Lippincott & Co.

-

Date

July 1, 1865

from Dec. 15, 1865

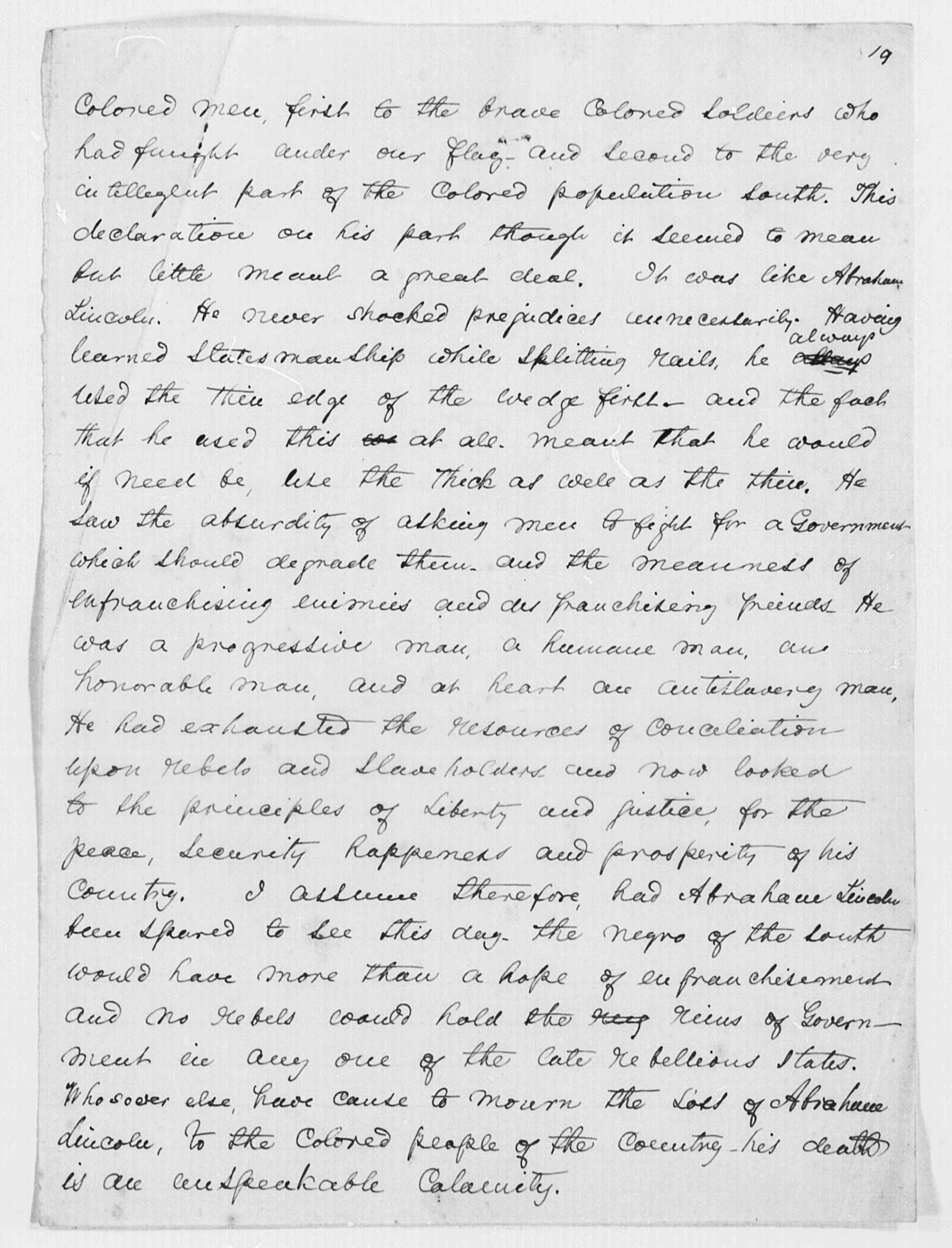

Abraham Lincoln, a Speech

-

Full Title

Abraham Lincoln, a Speech

-

Description

In this speech, Frederick Douglass reflected on how the outpouring of joy at the conclusion of the Civil War turned to mourning with Lincoln’s assassination. His death, according to Douglass was not only tragic, but also prevented recently freed slaves and African Americans from gaining the ear of wise and well-intentioned leader. Towards the end of his speech, Douglass pondered how life would have been different had Lincoln not perished in April, lamenting that his death was a great blow against African American rights.

-

Transcription

Colored men, first to the brave Colored Soldiers who had fought under our flag and second to the very intelligent part of the Colored population South. This declaration on his part though it seemed to mean but little meant a great deal. It was like Abraham Lincoln. He never shocked prejudices unnecessarily. Having learned Statesmanship while splitting rails, he always used the thin edge of the wedge first, and the fact that he used this at all meant that he would if need be, use the thick as well as the thin. He saw the absurdity of asking men to fight for a Government which should degrade them, and the meanness of enfranchising enemies and de-franchising friends. He was a progressive man, a humane man, an honorable man, and at heart an antislavery man. He had exhausted the resources of conciliation upon rebels and slaveholders and now looked to the principles of Liberty and justice, for the peace, security, happiness and prosperity of his Country. I assume therefore, had Abraham Lincoln been spared to see this day, the negro of the South would have more than a hope of enfranchisement and no rebels could hold the reins of Government in any one of the late rebellious States. Whosoever else have cause to mourn the loss of Abraham Lincoln, to the Colored people of the Country his death is an unspeakable calamity.

[Transcription by: Evan Laugen, Chandra Manning's class, Georgetown University]. -

Source

Frederick Douglass Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Frederick Douglass. "Abraham Lincoln, a Speech". Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/812

-

Creator

Frederick Douglass

-

Date

Late December 1865

from Dec. 15, 1865

Abraham Lincoln, a Speech

-

Description

In this speech, Frederick Douglass reflected on how the outpouring of joy at the conclusion of the Civil War turned to mourning with Lincoln’s assassination. His death, according to Douglass was not only tragic, but also prevented recently freed slaves and African Americans from gaining the ear of wise and well-intentioned leader. Towards the end of his speech, Douglass pondered how life would have been different had Lincoln not perished in April, lamenting that his death was a great blow against African American rights.

-

Source

Frederick Douglass Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

-

Rights

This item is in the public domain and may be reproduced and used for any purpose, including research, teaching, private study, publication, broadcast or commercial use, with proper citation and attribution.

-

Creator

Frederick Douglass

-

Date

December 15, 1865

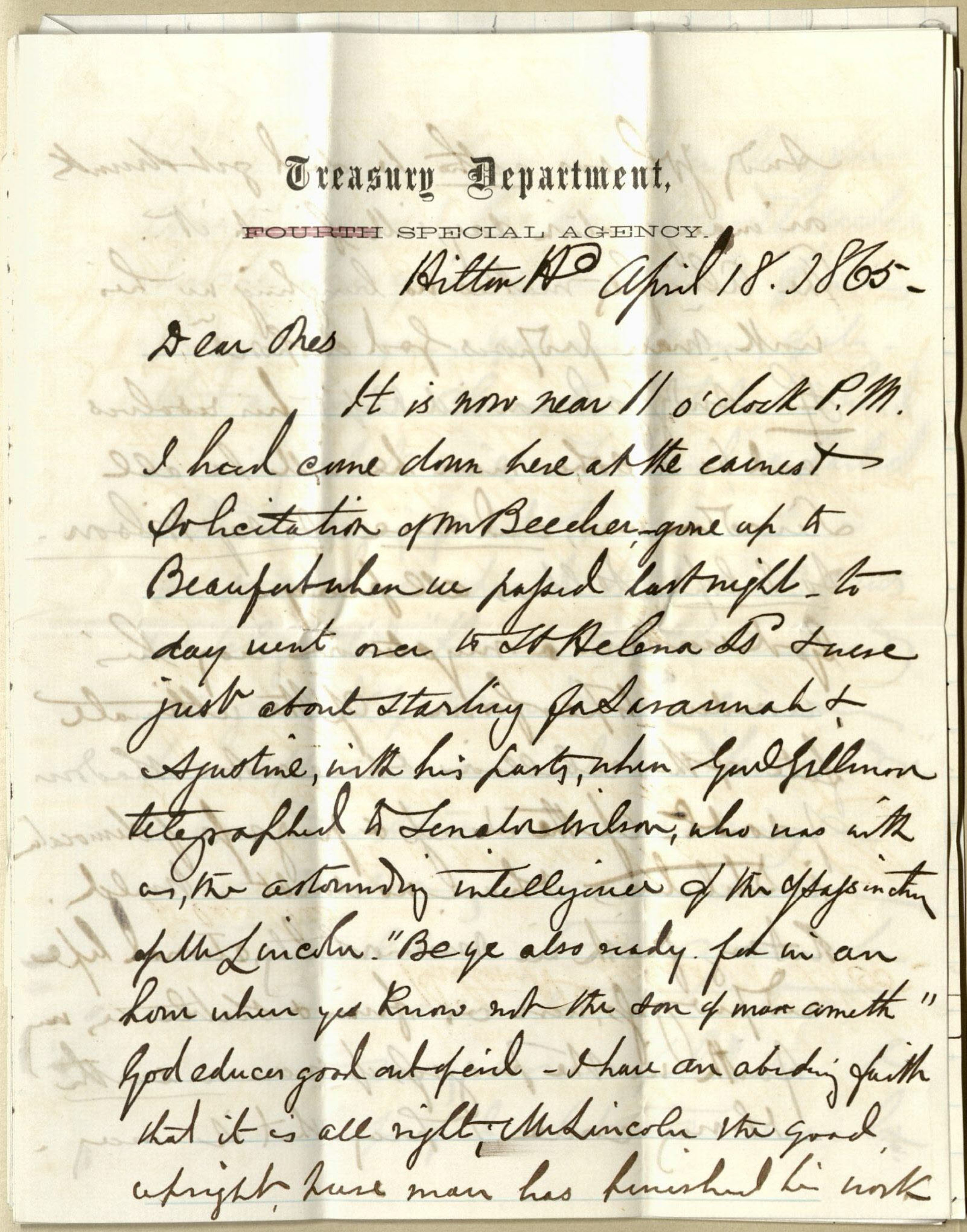

from Apr. 18, 1865

Albert Browne to “Dear Ones”

-

Full Title

Albert Browne to “Dear Ones"

-

Description

Abolitionist Albert Browne, a U.S. Treasury official at Hilton Head, South Carolina, at the end of the Civil War, wrote home to his family about the events of the few days since the Lincoln assassination. He stated, “O how much I have lived in these few days!”

-

Source

Browne Family Papers, Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

-

Rights

Use of this item for research, teaching, and private study is permitted with proper citation and attribution. Reproduction of this item for publication, broadcast, or commercial use requires written permission.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Albert Gallatin Browne. "Albert Browne to “Dear Ones"". Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/692

-

Creator

Albert Gallatin Browne

-

Date

April 18, 1865

from Apr. 18, 1865

Albert Browne to “Dear Ones"

-

Description

Abolitionist Albert Browne, a U.S. Treasury official at Hilton Head, South Carolina, at the end of the Civil War, wrote home to his family about the events of the few days since the Lincoln assassination. He stated, “O how much I have lived in these few days!”

-

Source

Browne Family Papers, Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

-

Rights

Use of this item for research, teaching, and private study is permitted with proper citation and attribution. Reproduction of this item for publication, broadcast, or commercial use requires written permission.

-

Creator

Albert Gallatin Browne

-

Date

April 18, 1865

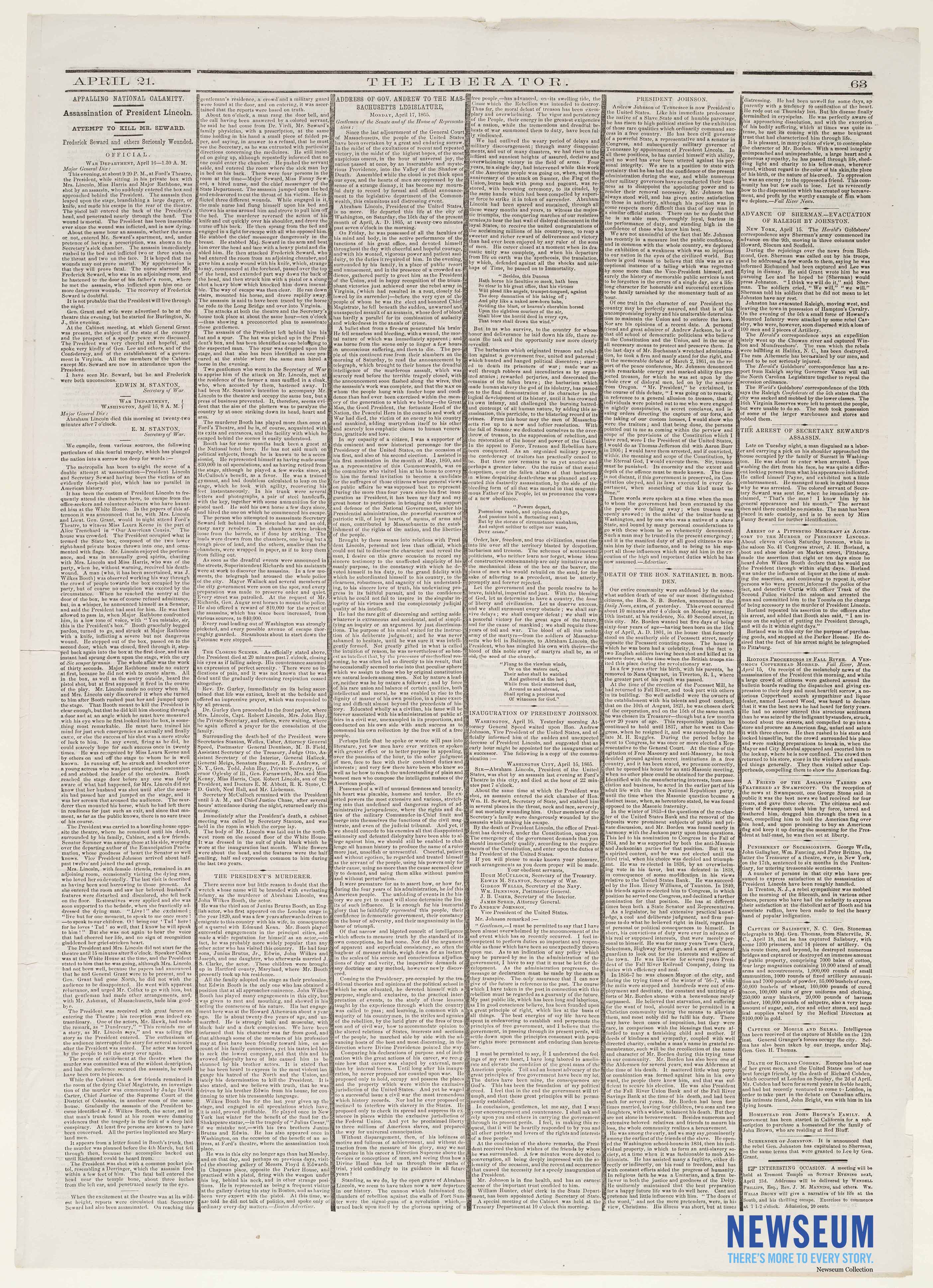

from Apr. 21, 1865

The Liberator, April 21, 1865

-

Full Title

The Liberator, April 21, 1865

-

Description

William Lloyd Garrison's abolitionist newspaper provides extensive details on the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and the attempted assassination of Secretary William Henry Seward. It contains the 1:30 a.m. official dispatch from Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to Major General John A. Dix, as well as the 8:00 a.m. dispatch reporting Lincoln's death. Known as "mourning rules," the wide vertical lines between the newspaper columns represent grief over the loss of an important person.

-

Source

HN-1865-011108B

-

Rights

Use of this item for research, teaching, and private study is permitted with proper citation and attribution as follows: Courtesy, Newseum Collection. Reproduction of this item for publication, broadcast, or commercial use requires written permission. For permission, please contact us at artifacts@newseum.org.

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Wm. Lloyd Garrison. "The Liberator, April 21, 1865". Wm. Lloyd Garrison. Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/630

from Apr. 21, 1865

The Liberator, April 21, 1865

-

Description

William Lloyd Garrison's abolitionist newspaper provides extensive details on the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and the attempted assassination of Secretary William Henry Seward. It contains the 1:30 a.m. official dispatch from Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to Major General John A. Dix, as well as the 8:00 a.m. dispatch reporting Lincoln's death. Known as "mourning rules," the wide vertical lines between the newspaper columns represent grief over the loss of an important person.

-

Source

HN-1865-011108B

-

Rights

Use of this item for research, teaching, and private study is permitted with proper citation and attribution as follows: Courtesy, Newseum Collection. Reproduction of this item for publication, broadcast, or commercial use requires written permission. For permission, please contact us at artifacts@newseum.org.

-

Creator

Wm. Lloyd Garrison

-

Publisher

Wm. Lloyd Garrison

-

Date

April 21, 1865

-

Material

Newspaper

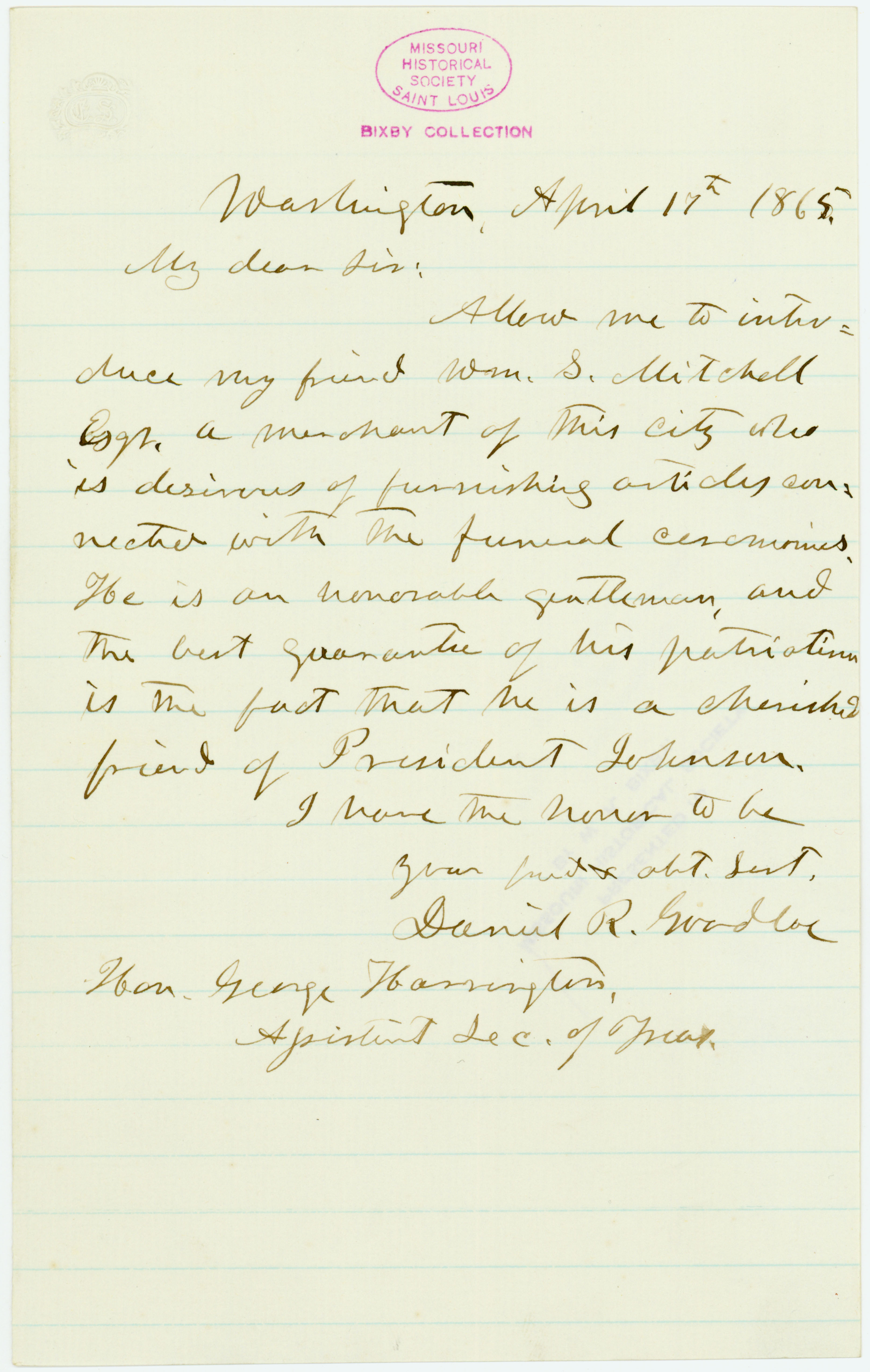

from Apr. 17, 1865

Daniel R. Goodloe to George Harrington

-

Full Title

Letter signed Daniel R. Goodloe, Washington, to Hon. George Harrington, Assistant Sec. of Treas., April 17, 1865

-

Description

States, "Allow me to introduce my friend Wm. S. Mitchell [William S. Mitchell] Esq. a merchant of this city who is desirous of furnishing articles connected with the funeral ceremonies. He is an honorable gentleman, and the best guarantee of his patriotism is the fact that he is a cherished friend of President Johnson. . . ." Regarding plans for Abraham Lincoln's funeral.

-

Transcription

Washington, April 17th 1865.

My dear Sir;

Allow me to introduce my friend Wm. S. Mitchell Esqr, a merchant of this city who is desirous of furnishing articles connected with the funeral ceremonies. He is an honorable gentleman, and the best guarantee of his patriotism is the fact that he is a cherished friend of President Johnson.

I have the honor to be

Your most obt. svt.

Daniel R. Goodloe

Hon. George Harrington,

Assistant Sec. of Treas.

[Transcription Team: Summer D., Joslyn P., Kaylee R., Brianna J.]

[New Hampton Middle School] -

Source

George R. Harrington Papers, Missouri History Museum Archives, St. Louis.

-

Rights

Goodloe, Daniel R. (Daniel Reaves), 1814-1902

-

Tags

-

Cite this Item

Goodloe, Daniel R. (Daniel Reaves), 1814-1902. "Letter signed Daniel R. Goodloe, Washington, to Hon. George Harrington, Assistant Sec. of Treas., April 17, 1865". Remembering Lincoln. Web. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://rememberinglincoln.fords.org/node/526

from Apr. 17, 1865

Letter signed Daniel R. Goodloe, Washington, to Hon. George Harrington, Assistant Sec. of Treas., April 17, 1865

-

Description

States, "Allow me to introduce my friend Wm. S. Mitchell [William S. Mitchell] Esq. a merchant of this city who is desirous of furnishing articles connected with the funeral ceremonies. He is an honorable gentleman, and the best guarantee of his patriotism is the fact that he is a cherished friend of President Johnson. . . ." Regarding plans for Abraham Lincoln's funeral.

-

Source

George R. Harrington Papers, Missouri History Museum Archives, St. Louis.

-

Rights

Goodloe, Daniel R. (Daniel Reaves), 1814-1902

-

Creator

Goodloe, Daniel R. (Daniel Reaves), 1814-1902

-

Date

April 17, 1865